☆ ☆ ☆ A Happy New Year in 2019 to all our Members! ☆ ☆ ☆

Welcome to the WDAS monthly newsletter for January 2019: a digest of the month's latest contributions to our website. Below you'll find Society News, Sky Notes and the return of Mark's feature article Crossing the Line; along with event details and details of this month's Lunar Eclipse.

(Reminder: this month's WDAS meeting is on the 2nd Tuesday of the month.)

Society News

This year’s society Christmas meal at the Hare and Hounds was once again a convivial occasion.

Nine members made it to the festive banqueting table, the taxi service provided by Mark and Saul ran like clockwork, shaming the normal taxi services. Besides Mark and Saul, Andy L, John L, Keith, Lee, and Victor all made it, along with Barbara and Mark, their first time.

The evening proved most enjoyable, crackers with party hats, pathetic jokes and trivia and novelty plastic things. Crackers sure are not what they used to be. The food though was delicious and, apart from some veg, plates went back pretty much empty. There were no menu issues either, so Mark had correctly placed the orders. With people driving etc, the wine cellar was not emptied this year, and just a couple of bottles were shared out amongst us... sort of.

Here’s to next year’s event.

Did anyone spot any Geminid meteors?

(Publisher’s note: Andi in Tenerife raises his hand, smugly.)

The evenings (and early part of the mornings) on the relevant dates, were pretty cloudy. The dawn of the 14th was clearer, but at 06:45h skies were beginning to lighten and Mark only saw two (one of these wasn’t a Geminid), so hopefully someone may have fared better.

Essential work on the Bruce Observatory is once again required in order to maintain the integrity of the building itself.

Essential work on the Bruce Observatory is once again required in order to maintain the integrity of the building itself.

The telescope and mount itself is in pretty good working order (maybe a good clean required) but the shutters, guttering, south side wall, dome felting and exterior laths all require attention.

Having been in contact with the college, a loose agreement may have been agreed whereby they would be willing (in the main) to provide funding for materials, as long as we carry out the work.

It is hoped to fully assess what is actually required over the Christmas period, hopefully reporting back at the next meeting in January.

There are not too many copies of night scenes 2019 remaining. If you would like a copy it’s just £4 to society members and £6 otherwise. They are an indispensable guide for the astronomical year ahead, so don’t delay, once gone that’s it.

Sky Notes

In this month's Sky Notes:

- Planetary Skylights

- Moon: Total Lunar Eclipse

- Meteors

- Comets

- Earth at Perihelion

- January 2019 Sky Charts

Planetary Skylights

Morning

The dawn sky is the place for planetary action as the New Year commences.

Venus totally dominates the early morning scene, a brilliant object across in the SSE that cannot be missed. Through a telescope look for the pleasing crescent phase, and as it’s a morning object see how long you can continue viewing Venus as skies brighten, you will be taken aback.

Venus totally dominates the early morning scene, a brilliant object across in the SSE that cannot be missed. Through a telescope look for the pleasing crescent phase, and as it’s a morning object see how long you can continue viewing Venus as skies brighten, you will be taken aback.

If you have a flat South-East horizon you will also spot conspicuous Jupiter which is now making inroads into the dawn sky lower left of Venus. It is still rather low to appreciate through a telescope, but there will be plenty of time to view Jupiter telescopically.

If you have a flat South-East horizon you will also spot conspicuous Jupiter which is now making inroads into the dawn sky lower left of Venus. It is still rather low to appreciate through a telescope, but there will be plenty of time to view Jupiter telescopically.

For the first few days of January elusive Mercury will still be visible, but you will need a flat SE aspect to spot it lower left of Jupiter. A slender waning crescent moon lies above/right of Mercury on the 4th at 07:30-07:40h. The day before the crescent moon is above left of Jupiter and the day before that it lies lower left of Venus.

For the first few days of January elusive Mercury will still be visible, but you will need a flat SE aspect to spot it lower left of Jupiter. A slender waning crescent moon lies above/right of Mercury on the 4th at 07:30-07:40h. The day before the crescent moon is above left of Jupiter and the day before that it lies lower left of Venus.

Then at the end of January watch as the Crescent Moon again resides between Jupiter and Venus, by which time Jupiter and Venus have swapped places in the morning sky. Keep tabs on the pair over the course of the month as they draw closer together, with a spectacular conjunction on Jan 22nd when they are separated by 2.5 degrees. View around 7:15-07:30h.

Then at the end of January watch as the Crescent Moon again resides between Jupiter and Venus, by which time Jupiter and Venus have swapped places in the morning sky. Keep tabs on the pair over the course of the month as they draw closer together, with a spectacular conjunction on Jan 22nd when they are separated by 2.5 degrees. View around 7:15-07:30h.

Evening

Mars continues to head eastwards along the ecliptic, and spends January moving up through Pisces and toward Uranus (next month). Telescopically glimpses of darker markings are possible, however as Earth continues to draw further away from the red planet, such views increasingly fall into the domain of larger apertures and imaging devices. The Moon resides below Mars on the 12th.

Mars continues to head eastwards along the ecliptic, and spends January moving up through Pisces and toward Uranus (next month). Telescopically glimpses of darker markings are possible, however as Earth continues to draw further away from the red planet, such views increasingly fall into the domain of larger apertures and imaging devices. The Moon resides below Mars on the 12th.

Of the outer gas giants Uranus is well placed for observation during the evening across in the SSW. It has just moved over the border from Aries into Pisces and resides less than 1.5 degrees north of Omicron Piscium (look for ‘Torcular’ on star charts). It can be picked out in binoculars, but through a telescope you will easily spot the ghoulish soft green hue of its very small disk.

Of the outer gas giants Uranus is well placed for observation during the evening across in the SSW. It has just moved over the border from Aries into Pisces and resides less than 1.5 degrees north of Omicron Piscium (look for ‘Torcular’ on star charts). It can be picked out in binoculars, but through a telescope you will easily spot the ghoulish soft green hue of its very small disk.

Neptune is becoming more difficult to track down as slides further down into the SW murk. View in the first half of the month around 6pm. It resides approximately a binocular field lower left of the asterism known as the ‘water jar’ in constellation of Aquarius’ and between the stars lamda and phi Aquarii, and on a smaller scale forms a triangle with 81 and 82 Aquarii. You will require a telescope to identify it, appearing as a tiny blue/grey disk.

Neptune is becoming more difficult to track down as slides further down into the SW murk. View in the first half of the month around 6pm. It resides approximately a binocular field lower left of the asterism known as the ‘water jar’ in constellation of Aquarius’ and between the stars lamda and phi Aquarii, and on a smaller scale forms a triangle with 81 and 82 Aquarii. You will require a telescope to identify it, appearing as a tiny blue/grey disk.

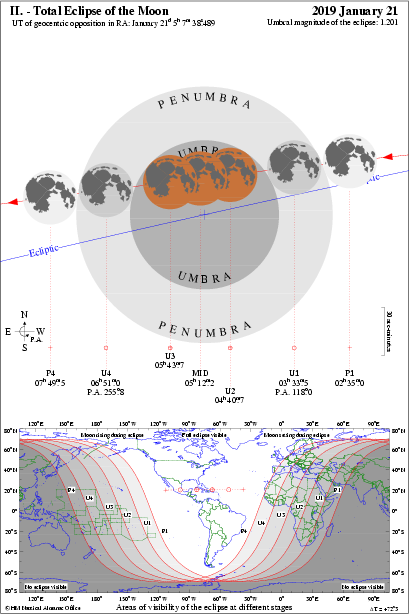

Total Lunar Eclipse

You will have to set the alarm for the highlight of the month, when there is a total lunar eclipse during the early morning hours of the 21st.

- Totality is centred on 05:12h, but…

- The penumbral part of the eclipse, when the moon sits in very slight shadow, begins shortly after 02:30h.

- Things become noticeable after 03:45h when the moon moves into Earth’s penumbral (darker) shadow, with…

- Totality commencing from 04:40h and lasting until 05:43h.

- By 06:50h the umbral part of the eclipse is over, with…

- The Moon completely leaving Earth’s shadow by 07:45am, in rapidly brightening skies.

If we are fortunate and skies are clear, the Moon should turn a lovely burnt orange colour, although atmospheric conditions on Earth will have a bearing on the actual hue. With the Moon reaching perigee later that day it will no doubt be called a super eclipse moon by the media.

Meteors

The hangover from New Year Eve has barely departed before we have one of the more prolific meteor showers.

The Quadrantids (active between Jan 1- 6th) peak in the early morning hours of the 4th and with the moon new on the 6th, weather permitting, conditions should be ideal.

Yes, I know 02:00h is rather early, or very late, for most of us, however the great thing about the Quadrantids is that the peak is relatively short lived, so if you are up and about at that time and skies are clear, you are pretty much guaranteed of seeing upwards of 40-50 per hour (the upper ZHR is actually 110 per hour).

The Quadrantids appear to radiate from the now defunct constellation of Quadrans Muralis, which was removed from sky charts in 1922, but used to lie at the junction between Hercules, Bootes and Ursa Major. This position in the sky is located low to the North at the time of the peak, so do not concentrate on this aspect if viewing.

Comet 46P Wirtanen

Apparently 46P has been visible to the naked eye from dark locations. Such locations can be found in the vicinity of Whitby, but same cannot be said for clear skies, especially ones required when:

- You are awake, and not given up hope and gone to bed, and

- When the moon does not totally drown out the comet. Patience, patience, we have experienced this before, it will come good, I’m sure, surely?

So fingers crossed and repeat after me, “It will come good... it will come good…", perhaps holding a small dog and clicking heels together, just to be on the safe side.

Coming down to Earth and sanity, Comet Wirtanen will spend the early part of January (realistically the last chance to view it in binoculars) heading across Lynx and into the ‘head’ end of Ursa Major. The comet will have faded a little, but will still be readily visible in binoculars as a fuzzy patch.

Comet 46P was taken by Mike Welham from his observatory in Melsonby. Those of you who went to the Leeds Astromeet or this year’s FAS Convention will know Mike, an honorary member of the society.

Stop Press

- Then on Christmas Eve 2018, around tea time, Mark spotted 46P as darkness fell and before the Moon rose. The comet was above left of Capella and through 15x70 binoculars appeared surprisingly large, round and very diffuse. (The size was roughly equal to that of the ‘box’ in the Pleiades.) Mark managed to take a few shots with his DLSR on a tripod, but on initial inspection it’s difficult to make out.

- Mark actually saw the comet again tonight Dec 27th – quite diffuse and we had to travel out of town to a darker location in order to spot it in binoculars. It appeared diffuse, quite large roughly circular patch, not as bright or as big as the Andromeda galaxy. Saw it in 7x50, 15x70, and 7x40 image stabilizer binocs. 7;20pm 27th December heading towards Lynx. Location: Old railway line crossing High Hawsker.

Earth at Perhelion

Finally, on Jan 3rd (00:19h) Earth reaches Perihelion (closest to the Sun in its orbit) some 147 million km (91.4 million miles) distant.

The intensity of solar radiation averaged out across the globe is 7% greater, around this time of year than it is in summer, but the fact we are 3 million miles closer in January has hardly any bearing on the temperature we experience.

This always comes as a surprise to non-astronomers, many of whom assume that Earth is furthest from the Sun in winter. It is the axial tilt of our planet that dictates the temperature especially at mid latitudes on the globe. Here in the northern hemisphere, which is tilted away from the Sun in winter, the angle at which the Sun’s rays strike the surface is much shallower, and the intensity of the radiant heat, and not radiation is much diluted. Hence, days are shorter and feel cooler.

January 2019 Sky Charts

|

Looking North

Mid-January - 20:00h |

Looking South |

|

Looking East

Mid-January - 20:00h |

Looking West

Mid-January - 20:00h |

|

Northern Aspect

Mid-January - 20:00h |

Southern Aspect

Mid-January - 20:00h |

| Looking North (Early) Mid-January- 06:00h |

Looking South (Early) Mid-January- 06:00h |

Additional Image Credits:

- Planets and Comets where not otherwise mentioned: NASA

- Sky Charts: Stellarium Software

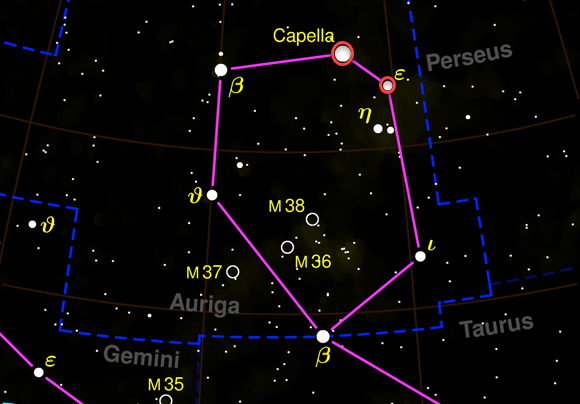

Continuing the tour of stellar objects crossing the meridian line this month: Capella from the constellation Auriga - the sixth brightest star in the night sky; and Epsilon Aurigae - an unusual binary system that lies just below it.

Star: Capella (Alpha Aurigae), Chief Star of Auriga the Charioteer

Easily visible unassisted.

Capella (Alpha Aurigae) is the chief star in Auriga the charioteer. It is sometimes known as the goat star, as Auriga is often depicted with a goat on his shoulders and holding two kids. Capella is the sixth brightest star in the sky (apparent mag of 0.08). The only other stars in the northern celestial hemisphere brighter, are Arcturus in Boötes and Vega in Lyra, although Sirius which can be seen from northern latitudes in winter and is the brightest star in the heavens also surpasses Capella. It lies approximately 42.5 light years from earth.

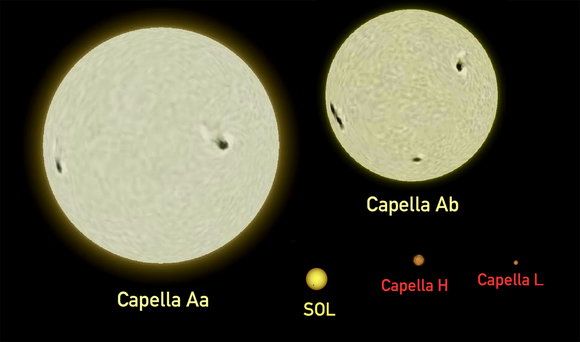

When viewed Capella appears to be a single star, however it is actually a quadruple star system made up of two binary pairs, the stars Capella Aa, Capella Ab are one pair and Capella H, and Capella L, the other. Capella Aa and Capella Ab, are two bright yellow giant stars, both of which are around 2.5 times as massive as the Sun. The second pair, Capella H and Capella L, lie around 10,000 astronomical units from the first pair and are faint, small and relatively cool red dwarfs. (1 AU = 93 million miles =Earth - Sun distance) The system lies approximately 42.5 light years from earth

Capella Aa and Capella Ab are in a very tight circular orbit about 0.74 AU apart taking 104 days to do so. Capella Aa is the cooler and more luminous of the two with a spectral class K0III; it is around 75 times the Sun's luminosity and 12 times its radius. Ab is slightly smaller and hotter and of spectral class G1III; it is around 70 times as luminous as the Sun and 8.5 times its radius.

The Capella system is one of the brightest sources of X-rays in the sky, thought to come primarily from the corona of Capella Aa.

Capella was once the brightest star in the night sky (208,000 BC – 158,000 BC) and was then closer to our solar system, around 30 light years away. It would have had an apparent magnitude of −1.8, brighter than Sirius appears to us today.

You cannot miss Capella in the sky crossing high to the south near the zenith in January.

Comparison of Capella with our Sun ('sol')

Star: Epsilon Aurigae (ε Aurigae) or 'Almaaz'

Easily visible unassisted.

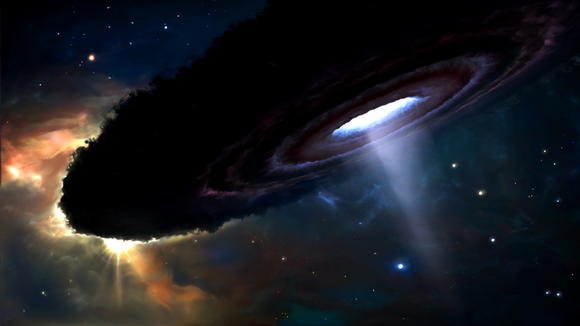

Epsilon Aurigae (ε Aurigae,) or Almaaz lies to the west Capella forming a triangle with eta and zeta aurigae, (Haedus and Saclateni) the ‘kids’. It is an unusual eclipsing binary system comprising an F0 supergiant and a companion which is generally accepted to be a huge dark disk orbiting an unknown object, possibly a binary system of two small B-type stars. The distance is still a little uncertain, but modern estimates place it approximately 1800 light years from Earth.

Epsilon Aurigae was first suspected to be a variable in 1821. About every 27 years, Epsilon Aurigae's brightness drops from an apparent visual magnitude of +2.92 to +3.83. This dimming lasts 640–730 days.

Epsilon Aurigae's eclipsing companion has been subject to much debate since the object does not emit as much light as is expected for an object its size. There are now two main explanations that can account for the known observed characteristics: a high mass model where the primary is a yellow supergiant of around 15 solar masses; and a low mass model where the primary is about 2 solar masses, and a less luminous evolved star.

As of 2008, the most popularly accepted model for this companion object is a binary star system surrounded by a massive, opaque disk of dust. Epsilon Aurigae A an F-type star has around 143 to 358 times the diameter of the Sun, and is around 38,000 times as luminous. The eclipsing component emits a comparatively insignificant amount of light, and is not visible to the naked eye. It is widely thought to be a dusty disc surrounding a class B main sequence star and is approximately 3.8 AU wide, 0.475 AU thick, and blocks about 70% of the light passing through it.

With Auriga located high overhead during the late evenings at this time of year, take a good look (binoculars are ideal) at these stars, which hide a great deal of their magnificence to our ordinary gaze.

Artists Impression of The ε Aurigae system during an eclipse (Brian Thieme)

In the News

NASA launched the spacecraft in 2006; it flew past Pluto in 2015, providing the first close-up views of the dwarf planet. After the successful flyby, NASA set their sights on a destination deep inside the Kuiper Belt, Ultima Thule is that object.

This Kuiper Belt object was discovered by the Hubble Space Telescope in 2014. Officially known as 2014 MU69, it got the nickname Ultima Thule in an online vote. When New Horizons first glimpsed the rocky iceball in August it was just a dot. Good close-up pictures should be available the day after the flyby.

New Horizons will make its closest approach in the wee hours of January 1st hurtling by within 3,500 kilometres (2,200 miles) of Ultima Thule at some 50,700 kph (31,500 mph). It will take about 10 hours to get confirmation that the spacecraft completed — and survived — the encounter. Hopefully, later on New Year’s day we shall get that, so keep an eye on the media. It will take almost two years for New Horizons to beam back all its data on Ultima Thule. A flyby of an even more distant world could be in the offing in the 2020s, if NASA approves another mission extension and the spacecraft remains healthy.

Events

Whitby School, Prospect Hill site, Main block, Room H1 (first along corridor from Hall).

In our monthly meetings, we review the night sky for the upcoming month using a Planetarium program, have talks and presentations on astronomy and space topics, and discuss future events. New members are welcome.

Observe the night sky with us at the Bruce Observatory, Whitby School

Observe the night sky with us at the Bruce Observatory, Whitby School

Observing Nights are held weather permitting: check for a relatively clear sky before leaving home. If in doubt, Mark can be reached on 07886069339

Please note the college drive gate is now operated via a electronic key code - so anyone wishing to attend must be at the car park at the top of the drive by 19:00hrs - unless an arrival time has been arranged with Mark/Keith.

Observe the night sky with us at the Bruce Observatory, Whitby School

Observe the night sky with us at the Bruce Observatory, Whitby School

Observing Nights are held weather permitting: check for a relatively clear sky before leaving home. If in doubt, Mark can be reached on 07886069339

Please note the college drive gate is now operated via a electronic key code - so anyone wishing to attend must be at the car park at the top of the drive by 19:00hrs - unless an arrival time has been arranged with Mark/Keith.

Observe the night sky with us at the Bruce Observatory, Whitby School

Observe the night sky with us at the Bruce Observatory, Whitby School

Observing Nights are held weather permitting: check for a relatively clear sky before leaving home. If in doubt, Mark can be reached on 07886069339

Please note the college drive gate is now operated via a electronic key code - so anyone wishing to attend must be at the car park at the top of the drive by 19:00hrs - unless an arrival time has been arranged with Mark/Keith.

Observe the night sky with us at the Bruce Observatory, Whitby School

Observe the night sky with us at the Bruce Observatory, Whitby School

Observing Nights are held weather permitting: check for a relatively clear sky before leaving home. If in doubt, Mark can be reached on 07886069339

Please note the college drive gate is now operated via a electronic key code - so anyone wishing to attend must be at the car park at the top of the drive by 19:00hrs - unless an arrival time has been arranged with Mark/Keith.