Welcome to the WDAS monthly newsletter for March 2017: a digest of the month's latest contributions to our website. Below you'll find Society News, Sky Notes and In-Focus articles printed in full. There's also future events, and trailers for other articles which appear in full on the website - just a click away!

On the website you'll also be able to comment on articles, and if you'd like to play an editorial role in creating new content, just let us know!

Society News

The date of the Vernal Equinox and officially the start spring in the northern hemisphere falls on March 20th this year. This is when the Sun's path - the ecliptic - first crosses the celestial equator on its apparent journey northwards into the sky.

The date of the Vernal Equinox and officially the start spring in the northern hemisphere falls on March 20th this year. This is when the Sun's path - the ecliptic - first crosses the celestial equator on its apparent journey northwards into the sky.

The orientation of the Earth at the spring or autumnal equinox is such that neither of the poles are inclined towards the Sun and all locations experience equal hours of daylight and darkness - hence the term equinox.

The Vernal Equinox is also known as the 'First point of Aries', as the Sun used to stand before the constellation of the Ram when it first crossed the celestial equator. Although still called the 'first point of Aries', today its location now resides in Pisces, a consequence of the effect known as precession - the Earth's slow wobble.

Over thousands of years our ancestors noted that certain star patterns rose just before the Sun at specific times and were considered significant for this very reason. Subsequently they were able to build a picture of the apparent path of the Sun against these constellations.

The narrow path upon which occasionally the Sun and Moon would meet giving rise to an eclipse, became known as the Ecliptic. The broader belt along which the 'wandering stars' or planets travelled was known as the Zodiac, so called because all 12 constellations located on it were associated with living creatures. Zodiac literally means 'Band of Animals'. Libra used to be considered being part of Scopius, the claws to be precise. Ophiuchus, the serpent bearer immediately following Scorpius was instead regarded as a zodiac group. Ever since the stars of Libra were elevated in status, Ophiuchus, being surplus to requirements, was ditched, much to the relief of astrologers.

If you find it difficult to remember the order of the zodiac constellations, then the following rhyme may be of use.

The Ram, the Bull, the Heavenly twins

and next the Crab the Lion shines,

The Virgin, and the Scales.

Scorpion, Archer and Sea goat,

the man who pours the water out

and Fish with glittering tails.

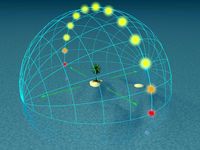

The first of the events (a last minute unscheduled event on the 18th) was predominantly clouded out. Mark and Keith therefore enrolled the scouts in helping to demonstrate the scale solar system.

The first of the events (a last minute unscheduled event on the 18th) was predominantly clouded out. Mark and Keith therefore enrolled the scouts in helping to demonstrate the scale solar system.

There were certainly plenty of them, so they had to be split into two groups. The demos went well and no scouts were lost in the sea.

Well we are going to be busy late March and into April.

As you know we have been invited to another ‘Star Night’ hosted by Eskdale School. This year’s event will take place on Wednesday 22nd of March, starting from 19:00h. The York University people will be on hand with the inflatable planetarium, and there will be food, soup, cakes, drinks etc available.

As you know we have been invited to another ‘Star Night’ hosted by Eskdale School. This year’s event will take place on Wednesday 22nd of March, starting from 19:00h. The York University people will be on hand with the inflatable planetarium, and there will be food, soup, cakes, drinks etc available.

On March 28th we have been invited to visit the Whitby Scouts at the Scout hut on Spring Vale. (Or possibly at Boggle Hole: it's a bit uncertain at the moment - contact Mark to make sure of the latest!) This is to prepare them for their astronomy badges. 18:15pm.

On March 28th we have been invited to visit the Whitby Scouts at the Scout hut on Spring Vale. (Or possibly at Boggle Hole: it's a bit uncertain at the moment - contact Mark to make sure of the latest!) This is to prepare them for their astronomy badges. 18:15pm.

After been contacted by Elizabeth Labelle, Assistant Head Teacher (Phase III) of Ayresome Primary School & Lego Innovation Studio. We shall be hosting an event for visiting pupils up at the Whitby Youth Hostel on April 12th. You may recall we did a similar event last year. The start time is around 20:30pm.

After been contacted by Elizabeth Labelle, Assistant Head Teacher (Phase III) of Ayresome Primary School & Lego Innovation Studio. We shall be hosting an event for visiting pupils up at the Whitby Youth Hostel on April 12th. You may recall we did a similar event last year. The start time is around 20:30pm.

A new venue now, as we have been asked by Andy Martin, managing director of Northcliffe and Seaview Holiday parks, High Hawsker as to whether we can host a star party event there. We can, and it is Good Friday – April 14th from 20:30pm.

A new venue now, as we have been asked by Andy Martin, managing director of Northcliffe and Seaview Holiday parks, High Hawsker as to whether we can host a star party event there. We can, and it is Good Friday – April 14th from 20:30pm.

It would not surprise me if further visits were also forthcoming, but for the moment my crystal ball has gone cloudy. Let us hope that it’s the only cloud we encounter.

All being well Paul is set to return to Whitby in May. The venue will be the college main hall (Whitby college as was) May 9th is the date ‘inked in’ and we will be looking to start around 19:30pm. No definite topic as yet, although Paul has suggested an updated talk on Voyager, to coincide with its 40th anniversary since launch.

It's been a big news week for space, so let's have a round-up in the Newsletter.

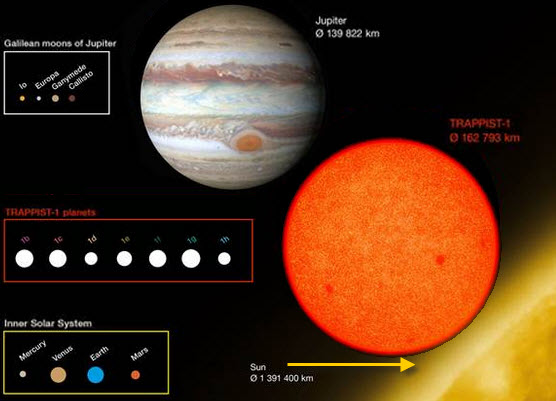

Seven Earth-sized Planets around a Supercool Dwarf Star

It’s not often that astronomers find Earth-like planets around other stars. There are a lot of reasons for that. But last spring, a team of researchers announced that they’d found three new Earth-sized, rocky planets with temperatures moderate enough for liquid water, and therefore life as we know it to survive upon. And all those planets are orbiting the same star, which is only 39 light years away!

This week, the group made another big announcement: they found four more planets orbiting that same star. And three of the new planets they found are also Earth-sized, rocky, and at the right temperature for life to survive. They published their findings in the journal Nature.

This is the solar system you want to go to. You could have so many planets! The planets’ parent star is named TRAPPIST-1, and it’s amazingly cool. In fact, you could call it "ultra cool". Because that is how it is classified: it’s an ultracool dwarf star. Ultracool dwarfs aren’t much bigger than Jupiter, and they’re just barely hot enough to convert hydrogen into helium, which is how they produce the energy that keeps them going.

Last spring was the first time we’d found planets around an ultracool dwarf, and now we have even more to add to the list, just around this one star. The team found the planets using a common method called transit photometry. When a planet passes in front of its star, it blocks a little of the star’s light, and astronomers can use those measurements to detect planets and figure out some basic information about them. After the first three planets were found around TRAPPIST-1, the team used telescopes on the ground and NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope to find the remaining four.

Size Comparison: Trappist-1 system vs Jupiter system vs Inner Solar System

Image credit: ESO/O. Furtak

Right now, we don’t know much about the planets besides their size, their density, and that they could be habitable, but we hope to learn a lot more in the coming years, especially with the launch of the James Webb Space Telescope. JWST, which is scheduled to launch next year, will be able to study the atmosphere of these distant planets, which will tell us more about their climate and if there could be liquid water on the surface.

Of course, finding planets where life might be able to survive doesn’t mean they actually harbour life. But with each new discovery, we’re learning that life-friendly environments are much more common in the universe than we once thought. And that includes water within our own solar system.

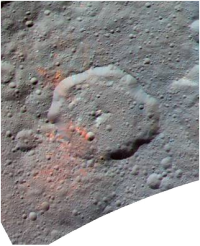

Organic Molecules found on Ceres and possibiliy of an Underwater Ocean

Ernutet Crater on Ceres: areas

coloured red rich in organics.

Image: NASA/JPL-Caltech/etc

Back in 2015, NASA’s Dawn spacecraft arrived at Ceres, a dwarf planet that’s the largest object in the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter. And last week, in a report published in the journal Science, Dawn researchers announced they’d found organic molecules, aka the building blocks of life, on Ceres’ surface.

Organic molecules are carbon containing molecules, which is the foundation for life as we know it. Dawn’s instruments weren’t able to detect exactly what kind of molecules were on the surface, but they’re probably tar-like molecules like kerite and asphaltite.

The probe found large concentrations of the molecules in two different craters - a total of 1400 square kilometres. It’s also possible that Ceres once had an ocean under its surface, though we don’t know if it still does. And it could have some internal heat left over from when it formed.

Combining organic molecules, liquid water, and heat is a pretty good recipe for life - so there’s a possibility that primitive life, like tiny microbes, could have developed on Ceres. It’s still important to remember that all we have at this point is evidence that Ceres has some of the ingredients for life, not that there actually are or ever were living things there. But with about four months left in Dawn’s mission, hopefully we’ll be learning a lot more about that crazy, unusual world.

SpaceX: Manned round-Moon mission announced

SpaceX Dragon to carry comme-

cial passengers beyond the Moon

and back in 2018. Image: SpaceX

And back here on Earth, it's been a big week for SpaceX. We discussed SpaceX in Andi's talk on terraforming Mars in February's Meeting, because SpaceX hopes to start taking paying passengers to start a colony on Mars within the next 10 years. This week SpaceX got two well-healed and paying passengers fly them around and beyond The Moon. It will be the first time anyone has been outside near-earth orbit since the end of the Moon missions approaching half a century ago.

And it's a kind of testament to Moon missions past and planned, that this week SpaceX launched their first rocket from Pad 39A at Kennedy Space Centre. Pad 39A is where some of the most important human spaceflight missions began, from Apollo 11 to the last space shuttle flight six years ago. One day, SpaceX hopes to launch the first human mission to Mars from that pad, so the fact that their first launch from 39A was a success is a good start to the next chapter of the launch pad’s story.

Not only did the capsule make it safely into space, but the rocket’s booster also had a picture-perfect landing back on the ground, meaning it can be reused for another mission. The experiments on board represent work from 800 scientists around the world, including projects about things like how wounds heal and how bacteria and stem cells grows in space. The capsule also included instruments, like SAGE-III, which will monitor the Earth looking for atmospheric ozone, and Raven, which will collect data to help future spacecraft dock automatically.

So between finding new Earth-like planets, looking for evidence of life on Ceres, announcing a manned trip round The Moon and launching lots of new experiments, it’s been a big week for space exploration.

The video and most of the material for this article was put together by YouTube channel "SciShow Space". You can support their work creating videos that help to teach the world about astronomy by sponsoring a dollar or two per month via their Patreon page.

In-Focus

The lighter evenings of April offer up an interesting stellar challenge, testing the observing dexterity of astronomers;- casual or otherwise in a race against time. Fear not, this is not a ‘faint fuzzy blob’ hunt, like the Messier marathon, the exact opposite in fact, more of a sprint really and should only take a few minutes to complete given suitable horizons, a fair wind and some sky knowledge.

This is all about spotting first magnitude stars; those ranked brightest in the sky and dotted around the twilight sky of early spring are no less than thirteen, more than at any other time of year. However the window of opportunity in which to identify these stellar jewels rapidly diminishes as we head deeper into April, from little over an hour at the start, to just fifteen minutes by mid month. You will however require a complete 360 degree unobstructed view of the horizon and complicating matters further, a number of planets may confuse the unwary.

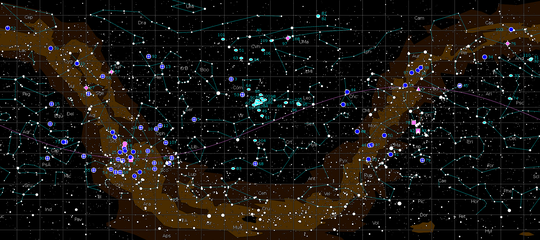

5-Minute Stellar Baker's Dozen Challenge of 1st Magnitude Stars (by Mark Dawson)

Click for full-size image with Key.

You will require clear views right around the horizon and complicating matters further, a number of bright planets may confuse the unwary.

Let us assume it is late March (post clock change i.e BST time) or early April, at which time twilight deepens around 9pm. Our first port of call lies over in the west, where the mighty hunter; Orion, is about to lose his right toe, marked by bright Rigel, (1) below the horizon. . A word of caution before we go any further. Two naked eye planets are to be found low in the west late March/early April - Mars and Mercury. Mars will have a distinct orange hue, Mercury may be harder to spot depending on what date you observe, so if the 'star' you are looking at doesn't seem to fit the constellation, well done, you have also spotted two planets.

Above Rigel, Orion’s three belt stars are aligned parallel to the west horizon, but the next star on our list, the conspicuous orange hue of Betelgeuse (3), is located above them. A hand span to the right of Betelgeuse and slightly closer to the horizon another orange star, Aldebaran (4) chief star in Taurus is visible in the ‘V’ of the Hyades cluster. Low in the WSW the brightest star in the sky – sparkling Sirius (5) should be quite unmistakable.

Having picked out this first clutch of stars, there is no time to waste, so raise your gaze somewhat higher, to pick out the next wave of luminaries.

Starting in the SW again seek out the bright solitary white hue of Procyon (6) in Canis Minor located above Sirius and to the left of Orion. Due west and higher still, Castor (7) and Pollux (8) denote the twins of Gemini, which is descending feet first down toward the horizon. At a similar altitude to Gemini further across in the WNW shines brilliant Capella (9) in Auriga, the only one of our bright seasonal winter stars not to set, being circumpolar from our latitude. Capella will spend the summer months arcing low above the north horizon and tricking the unwary into thinking it's the north star!

Turn and face due south, where midway up you will encounter bright Regulus (10) in the ‘sickle’ asterism of Leo. Our next two luminaries are located in the east. Due east, brilliant Arcturus (11) in the constellation of Bootes is very noticeable, its soft orange hue contrasting markedly with Sirius, the only star of the baker’s dozen brighter than it. Now for a test within a challenge, see how far into April you can spot both Sirius and Arcturus above the horizon at the same time! We still have three stars to locate, the first of which, Spica (2) chief star in Virgo, is just rising in the SE, so to spot it at the same time as the others a clear unobstructed view is required. Caution again- the very conspicuous 'star' above Spica is the planet Jupiter.

So, having viewed west, south and east, direct your gaze toward the North, where low in the North-East brilliant steely blue Vega (12) resides in the constellation of Lyra. Vega almost rivals Arcturus in apparent magnitude, but unlike the ‘guardian of the bear” it is circumpolar from Whitby’s latitude and to the unwary also masquerades as the north star during the winter months. Our final star, Deneb (13) is located just above the NNE horizon and appears much less brilliant than Vega but is by far the most distant and massive of the stars visited. It too is circumpolar and along with Vega constitutes two of the three stars forming the ‘summer triangle’.

There we have it, thirteen 1st magnitude stars visible all at the same time. The test shouldn’t take more than a few minutes to spot them all, but timing is crucial and being able to spot Spica, Rigel and Sirius at the same time is the key to accomplishing the task. Good Luck and clear skies.

The Man

Charles Messier was born in 1730 in the small provincial town of Badonviller in the independent dukedom of Salm; now in France near the German border (Lorraine). His family was one of the richest in the state, with high ranking positions and excellent connections, which would later be very helpful to Messier.

Charles Messier was born in 1730 in the small provincial town of Badonviller in the independent dukedom of Salm; now in France near the German border (Lorraine). His family was one of the richest in the state, with high ranking positions and excellent connections, which would later be very helpful to Messier.

In the middle or the 18th century, astronomy stood at the threshold of a great observational age. Astronomers grew increasingly familiar using telescopes to search the night sky, finding ever more faint and exotic looking nebulae, although at the time these fuzzy blobs were regarded as trivia, not being important and were certainly not understood. Comets were the fascination of the age, their discovery and subsequent observation occupying many observatories; bringing fame and fortune (to some extent) to their discoverer.

Messier’s interest in astronomy was kindled with the appearance of the six tailed comet of 1744. He was hooked and using family connections, at the age of 21 Messier travelled to Paris to work as an assistant draftsman and astronomical observational recorder to the astronomer Joseph-Nicolas Delisle. Messier was instructed in the use of astronomical instruments and by 1754 was an experienced observer continuing the work of Delisle after he retired. Messier was obsessed by comets, Messier saw the 1759 return of Halley’s comet and over the next 15 years most comet discoveries were made by Messier, and in all he claimed to have discovered 21, though this is now challenged.

By the 1760’s Messier was regarded as the leading French astronomer, he was a member of the Royal Society in London and the Berlin academy and was finally admitted to the French academy of Science in 1770. It was to this institute that Messier submitted his great catalogue, the works for which we remember Messier.

From around 1758 Messier had noted down all the fuzzy, nebulous objects he had encountered while searching for comets, these he listed and by 1781 his published catalogue contained 103 objects. Not all of these were actually discovered by Messier, some were noted by Pierre Mechain who was Messier’s contemporary, though Messier did check most of his colleague’s observations. Over the years this catalogue was revised and his final version published in 1781 contained 103 entries. Historical evidence collated between 1921 and 1966 credit Messier and Mechain with another 7 objects bringing the total accepted today to 110. In 1805 Mechain became the director of the Paris Observatory while Messier received the cross of the legion of honour from Napoleon. Messier died in 1817 at the age of 86 yrs.

The Menagerie

Messier once wrote: “what made me produce this catalogue was the nebula I had seen in Taurus 1758 while I was observing the comet of that year. The shape and brightness of that nebula reminded me so much of a comet, that, I undertook to find more of its kind to save astronomers from confusing this nebula with comets".

Little did Messier know that his faint nebula in Taurus (M1) would become one of the most observed objects in the heavens - the supernova remnant we call the Crab nebula.

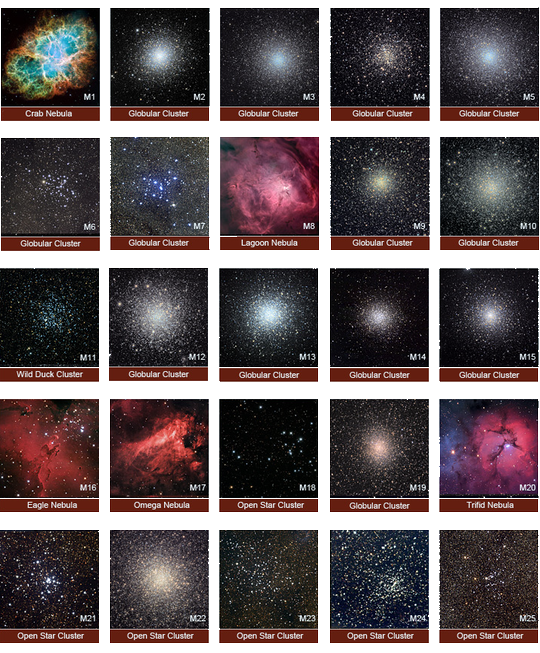

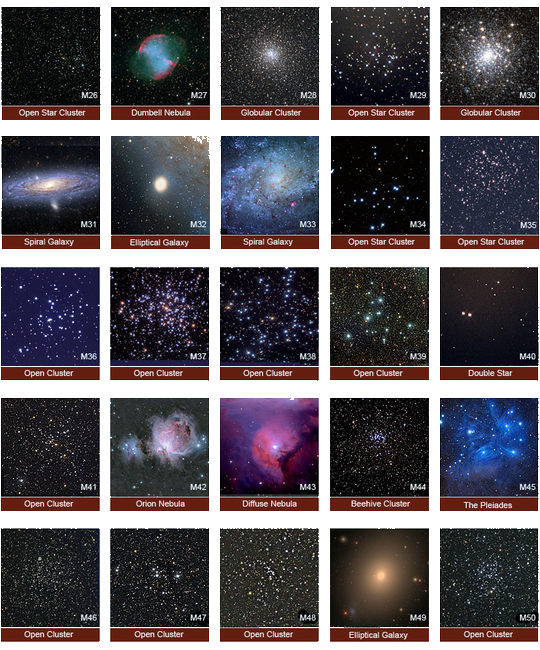

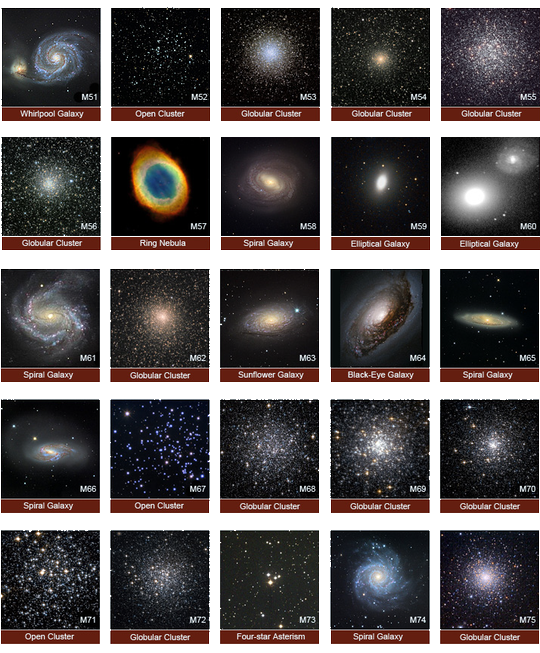

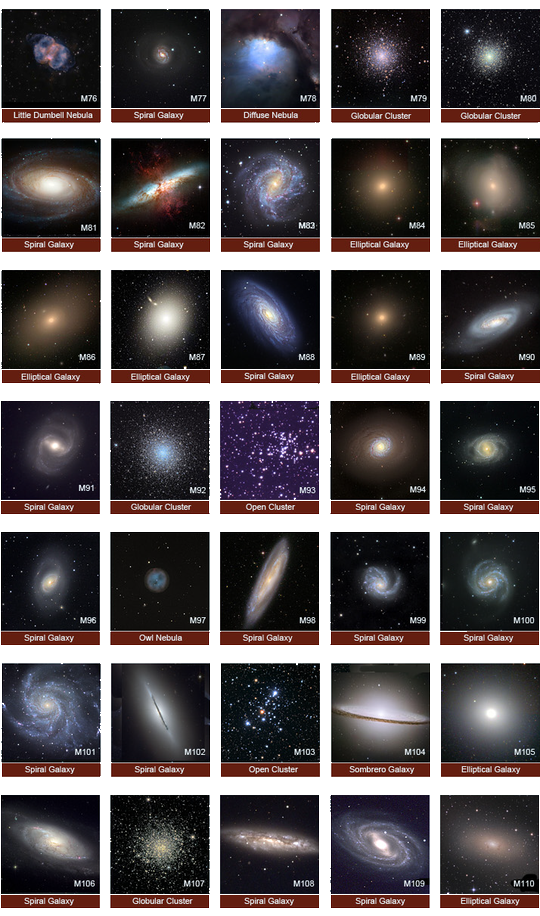

Of the 110 entries in Messier’s catalogue there are:

- 40 galaxies

- 29 globular clusters

- 28 galactic clusters

- 5 diffuse nebula,

- 4 planetary nebula

- 1 double star/asterism

- 1 bright patch of milky way at least 1 duplication and the catalyst of his work...

- 1 supernova remnant.

Above are small titled thumbnails of the Messier Catalogue (arranged by

telescopesinhistory.com). Click for a slightly larger view of each chunk of images.

Messier observed using various scopes, none of which were bigger than 8 inch, most were 3 or 4 inch in aperture and of inferior quality to today’s telescopes. Messier observed from the Hôtel de Cluny, in Paris, perhaps not ideal, but Parisian light pollution then would be much less interfering compared to the light blight of today.

The distribution of messier objects over the sky is far from uniform, clusters and nebula are bunched along the summer Milky Way, while galaxies abound in the spring sky. Many constellations contain no “M” numbers, Sagittarius contains 15. So how do you set about spotting as many “M”s as possible?

The Marathon

At least 80 messier objects can be seen on any given night, but due to their distribution around the sky, early spring, especially around the equinox, is suited better for observing as many as possible over the course of one night. This is because the majority of galaxies and galactic clusters located in the winter and spring sky are visible during the evening and pre midnight, whilst many globular clusters and nebulae are found before dawn, when summer constellations are on view.

The idea of the Messier marathon was actually invented in the early 1970’s, but it was not until the mid 80’s before the first complete run was accomplished. Before we go further it should be pointed out that completing the whole Messier marathon from the latitude of the UK over one night is impossible, indeed it can only be accomplished between latitudes 10 and 35 degrees north.(America, Southern Europe) Messier himself would certainly not have observed them all from Paris in one sitting. Our friend Paul Money is one of the few British amateur astronomers to have completed the challenge, though this was done from Portugal. My own personal record is a safe 72, but may have been 76...aaahh, the realm of galaxies, it is a minefield.

All objects must be seen through a scope or binoculars, preferably verified if attempting a serious marathon. Goto scopes are not allowed, although a Goto marathon would be rather interesting, especially to a marathon novice.

Timing is everything for a good Messier marathon. In March two objects; M74 a galaxy in Pisces, and M33 - Triangulum galaxy, have to be observed as soon as possible as twilight deepens. Whilst in the morning M69, 70, 54, 72, 73, 2, 75 and M55 all have to be picked out as soon as practicable before dawn washes them out. If attempting a 'good run' preparation is therefore essential for these evening and morning objects, whith little time to dwell on them. The midnight hours offer more time to do that.

Most of the objects are actually visible in a good pair of binoculars from a dark site. Only M91 is not. Certainly a 4inch refracter or reflector will be sufficient to reveal all, although a 8-10inch reflector makes life easier, preferably a dobsonian. A nebula filter is also desirable to help show up some of the more diffuse objects. You can of course familiarise yourself with all the objects at leisure over the course of a year before setting out on a serious attempt - something i would strongly advise. The messier marathon compliled below (half marathon perhaps?) is one i have completed on several occasions and concentrates on the brighter or more important objects accessible to binoculars and small scopes. This would constitute as a pretty decent first attempt. You may find the simplified map of all Messier objects helpful for quick location, but a good star atlas is really useful.

So, let’s begin our marathon in the west, as soon as twilight is deep enough to allow fainter stars to be visible. M74 and M33 will be the first objects to depart, followed shortly by M77 in Cetus, so start with these, which unfortunately on the night i tried were hidden in a low bank of cloud. So my first objects were easy

- M31 - the Andromeda galaxy, visible in binoculars, best with low powers in scopes, look carefully for M32 & M110 - both satellite galaxies of M31 and in the same low power field. Then drop down to M33 - the Pinwheel galaxy in Triangulum, use binoculars only from a dark location to spot,

- Northwards again to pick off M103 in Cassiopeia, then M34 - a fine galactic cluster, and M76 a small planetary nebula for scopes only, both in Perseus. M45 - the Pleiades, a wonder to behold with any low power instrument. Next ...

- M1 - locate zeta Tauri, the star marking the southern horn of Taurus. The Crab nebula is close by – telescopes only. Use averted vision to aid observation..

- M35 - A small hop up into Gemini to locate this large galactic cluster at the foot of the twins. . M36, 37, 38 - travel North into Auriga to hunt down this trio of open clusters, then... M42/43 - the Orion nebula in all its glory, use different powers, also look for M78 as well... M41 - down to Sirius, below which is the easy galactic cluster M41.

- M46/47 – galactic clusters are found a stride to the upper left.

- M50 – fine galactic cluster in Monocerus.

- Back to Gemini and turn left into Cancer. M44 - buzz buzz, it’s the Beehive cluster in Cancer, use higher powers to locate M67 below.

- And so to the “realm of galaxies”, the window on the universe, that lies at the junction of Leo, Coma and Virgo. Charts are vital here, and some practice, otherwise you will lose ‘the will’. Most of the objects are smidges of light and are quite close together, but check out M49, M83, 84, 86 and M87 (virgo), M63- the sunflower galaxy, M64 - the black eye galaxy and M94 –the starburst galaxy (canes venatici) Then M65 and M66 in Leo

- Move on and up into Ursa Major to locate the most Northerly of Messier’s objects, the galaxies of.M81/82 - a striking pairing in the same field of view at low powers, then into the Plough. M101= 102, harder than it should be, as are M97, M108, M109. M40 double star. M51- the whirlpool galaxy is tantalising, find it below the tip of the Plough’s handle,.. then travel towards the bright orange star Arcturus , on route taking in...

- M3 - a fine globular cluster, easy in binoculars and continuing on that trajectory locate...

- M5 - another pleasing globular

- M13 - in Hercules is a magnificent globular cluster and will take high powers... also in Hercules another globular cluster M92, is worth finding.

- M57 - the Ring nebula in Lyra is a must for scopes, also try finding M56. M27 - can be spotted with binoculars and does resemble a “Dumbbell” by which this planetary nebula is known as when viewed with a scope... not far below.

- M71 - a small globular in Sagitta is for scopes only... travel North again to pick off....

- M29 & 39 - are both so-so galactic clusters in Cygnus...

- Now it’s down to the South to pick out the best objects in Sagittarius. The diffuse nebulae of M20, (Trifid), M17, (Omega or horseshoe) and M8 (Lagoon) are all excellent, as too is the globular M22. For a more leisurely look at this whole region wait until August/ September time to become better aquainted

- M4 - in neighbouring Scorpius is also a fine globular, but the other objects can be difficult due to the Southerly declination.

- M72 and curious M73 chance pattern of faint stars - in Aquarius are fairly easy, and before it becomes to light try..M2 - also in Aquarius and an exceedingly fine globular... while to the North in Pegasus.. M15 - is another fine example of a globular cluster which rounds off our marathon nicely.

This is a solid foundation on which to build for anyone wishing to do so. Of course having a good knowledge of the sky goes without saying, but familiarisation of certain key groups of M objects when they are optimally placed (whatever time of year it may be) will greatly benefit the observer when ‘up against the clock’. This year (2017) would be a pretty decent time to attempt a marathon as the moon is new on March 28th. Hope for clear skies, wrap up well and see how many you can bag. Good Luck

Sky Notes

In this month's Sky Notes:

Planetary Skylights

Venus continues to dominate the evening sky – an unmistakeable beacon over in the SW. The crescent moon lies close to Venus on the first day of the month making for a pleasing visual treat, especially as Mars is also in the vicinity, indeed Venus and Mars are closest in the sky the following evening. Mars resembles an ochre star upper left of Venus.

Venus continues to dominate the evening sky – an unmistakeable beacon over in the SW. The crescent moon lies close to Venus on the first day of the month making for a pleasing visual treat, especially as Mars is also in the vicinity, indeed Venus and Mars are closest in the sky the following evening. Mars resembles an ochre star upper left of Venus.

As Venus descends, so Mercury climbs into the sky from mid month onwards, it’s best evening apparition of the year. Look for the elusive inner most planet at the back end of March from the 26th and into April. By then Venus will have all but departed, so the moon must serve as a guide to Mercury’s whereabouts. A thin crescent moon lies due west on the 29 and 30th, you will need to search in the evening twilight around 45 minutes after sunset. Locate the crescent and look a few degrees to the right at a similar height. If you spot what resembles a bright star you have tracked down Mercury. Use binoculars if you cannot initially spot it with the naked eye.

As Venus descends, so Mercury climbs into the sky from mid month onwards, it’s best evening apparition of the year. Look for the elusive inner most planet at the back end of March from the 26th and into April. By then Venus will have all but departed, so the moon must serve as a guide to Mercury’s whereabouts. A thin crescent moon lies due west on the 29 and 30th, you will need to search in the evening twilight around 45 minutes after sunset. Locate the crescent and look a few degrees to the right at a similar height. If you spot what resembles a bright star you have tracked down Mercury. Use binoculars if you cannot initially spot it with the naked eye.

Mars also resides low in the WSW upper left of Venus and Mercury. The red planet is readily visible to the naked eye and resembles an ‘ochre’ hued star. Telescopically Mars is well past its best for this apparition. View on the 1st when a crescent moon lies below and again on the 30th when Mars, Moon and Mercury form a triangle.

Mars also resides low in the WSW upper left of Venus and Mercury. The red planet is readily visible to the naked eye and resembles an ‘ochre’ hued star. Telescopically Mars is well past its best for this apparition. View on the 1st when a crescent moon lies below and again on the 30th when Mars, Moon and Mercury form a triangle.

As Mars and Mercury set around 9pm, so Jupiter emerges into the spring sky across in the east. Look for a very conspicuous beacon low in the SE. Currently Jupiter resides in the spring constellation of Virgo, above its chief star Spica. This means as night’s grow lighter, telescopic observations will be limited to the late evenings or even early mornings when Jupiter is higher to the south. Fortunately Jupiter always has something to offer, even for smaller apertures. Look for the banding on the disk and the attendant Galilean moons. On the 15th a waning crescent moon resides upper left of Jupiter.

As Mars and Mercury set around 9pm, so Jupiter emerges into the spring sky across in the east. Look for a very conspicuous beacon low in the SE. Currently Jupiter resides in the spring constellation of Virgo, above its chief star Spica. This means as night’s grow lighter, telescopic observations will be limited to the late evenings or even early mornings when Jupiter is higher to the south. Fortunately Jupiter always has something to offer, even for smaller apertures. Look for the banding on the disk and the attendant Galilean moons. On the 15th a waning crescent moon resides upper left of Jupiter.

Finally, Saturn rises in early morning hours and is best viewed telescopically around 4-5am low to the south. Saturn resides to the left of bright Antares, chief star of Scorpius. Look on the 20th when a waning crescent moon lies upper right of Saturn.

Finally, Saturn rises in early morning hours and is best viewed telescopically around 4-5am low to the south. Saturn resides to the left of bright Antares, chief star of Scorpius. Look on the 20th when a waning crescent moon lies upper right of Saturn.

Meteor Showers and Comets

No major showers this month; however at the very end of March you may spot a few Viginids, which are slow moving and have long paths. (Make up your own jokes) As usual early morning hours are best to spot any meteors. There are no comets readily visible this month.

March 2017 Sky Charts

Click each image to see a full-size Sky Chart:

Additional Image Credits:

- Planets and Comets where not otherwise mentioned: NASA

- Sky Charts: Stellarium Software

Events

Observe the night sky with us at the Bruce Observatory, Whitby School

Observe the night sky with us at the Bruce Observatory, Whitby School

Observing Nights are held weather permitting: check for a relatively clear sky before leaving home. If in doubt, Mark can be reached on 07886069339

Please note the college drive gate is now operated via a electronic key code - so anyone wishing to attend must be at the car park at the top of the drive by 19:00hrs - unless an arrival time has been arranged with Mark/Keith.

Observe the night sky with us at the Bruce Observatory, Whitby School

Observe the night sky with us at the Bruce Observatory, Whitby School

Observing Nights are held weather permitting: check for a relatively clear sky before leaving home. If in doubt, Mark can be reached on 07886069339

Please note the college drive gate is now operated via a electronic key code - so anyone wishing to attend must be at the car park at the top of the drive by 19:00hrs - unless an arrival time has been arranged with Mark/Keith.

Observe the night sky with us at the Bruce Observatory, Whitby School

Observe the night sky with us at the Bruce Observatory, Whitby School

Observing Nights are held weather permitting: check for a relatively clear sky before leaving home. If in doubt, Mark can be reached on 07886069339

Please note the college drive gate is now operated via a electronic key code - so anyone wishing to attend must be at the car park at the top of the drive by 19:00hrs - unless an arrival time has been arranged with Mark/Keith.

Observe the night sky with us at the Bruce Observatory, Whitby School

Observe the night sky with us at the Bruce Observatory, Whitby School

Observing Nights are held weather permitting: check for a relatively clear sky before leaving home. If in doubt, Mark can be reached on 07886069339

Please note the college drive gate is now operated via a electronic key code - so anyone wishing to attend must be at the car park at the top of the drive by 19:00hrs - unless an arrival time has been arranged with Mark/Keith.

Whitby School, Prospect Hill site, Main block, Room H1 (first along corridor from Hall).

In our monthly meetings, we review the night sky for the upcoming month using a Planetarium program, have talks and presentations on astronomy and space topics, and discuss future events. New members are welcome.