Welcome to the WDAS monthly newsletter for February 2015: a digest of the month's latest contributions to our website. Below you'll find Society News, Sky Notes and In-Focus articles printed in full. There's also future events, and trailers for other articles which appear in full on the website - just a click away!

On the website you'll also be able to comment on articles, and if you'd like to play an editorial role in creating new content, just let us know!

If you don't see images in this e-mail, look for a setting in your browser or e-mail reader to display them; and if you have any other problems reading the newsletter please let us know the browser or e-mail program you're using, and we'll see if we can fix it.

Society News

Paul Money with at his Publisher's

with expanded Night Scenes 2016

If you want to purchase a copy of Night Scenes 2016 (and i think you will) only 9 copies remain. The new edition has been expanded yet again, by 26 pages in fact. Compiled by Paul Money, this beautiful and indispensable colour almanac/ booklet is packed full of information on the coming astronomical year.

Each month now features a gate-fold 4 page spread, so there is far more information plus a dedicated page to the constellations and deep sky. If you want a copy reserve one now. We are setting a minimum price of £4.50 (although members have been buying them for £5 – they are so impressed with them). £6.50 for non members. (The normal retail price is £7.)

Please can any members who are intending to renew subs for the coming year, try to do so before the end of the month. Subs will be held at current levels:

Please can any members who are intending to renew subs for the coming year, try to do so before the end of the month. Subs will be held at current levels:

- £12 for Adults

- £6 for Under-16s

+ Night Scenes are £4.50 for Members

You can bring subs along to the W.D.A.S monthly meetings in December or January (or February at the very latest). If you cannot make the meetings, cheques are welcome. Please make them payable to: Whitby & District Astronomical Society. Please address to Mark Dawson: 33 laburnum Grove, Whitby. YO21 1HZ.

Many thanks for your continued support.

There is still time to renew annual subs before the next meeting if you havn’t already done so. Subs for 2015 are:

- Adults: £12

- Under 16s: £5

Any Cheques made payable to: Whitby & District Astronomical Society. Please address to Mark. Anyone wishing to purchase a copy of Night scenes 2015;- hurry, only a few remain. These are priced £4 for members and £6 for non members.

We have been invited to assist at the forthcoming ‘star night’ at Eskdale school on March 4th (the night after our March meeting).

The event, which will be similar to the one held 2 yrs ago at Eskdale, where I recall we tried in vain to spot comet Pannstars, will have the cosmodrome planetarium sited in the main hall. If skies are clear our scopes will be erected outside the back of the school, hopefully observing Jupiter, Orion etc.

The event, which will be similar to the one held 2 yrs ago at Eskdale, where I recall we tried in vain to spot comet Pannstars, will have the cosmodrome planetarium sited in the main hall. If skies are clear our scopes will be erected outside the back of the school, hopefully observing Jupiter, Orion etc.

If you can support the event, we aim to be there for around 18:30h. I believe hot soup, buns, tea and cakes will be available to warm the cockles should it be a chilly evening. The soup was most warming last time!

Sky Notes

Expected Visibility

Originally expected to be a reasonable binocular object under dark skies, comet Lovejoy, C/2014 Q2, has surprised us all, becoming a naked eye object visible in the winter sky to the South.

Now a word of caution, as of writing the comet is predicted to reach 4th magnitude during the 2nd and 3rd week of January, which means most people will still require a pair of binoculars to spot it due to light pollution. But you never know with comets, it may brighten even further. If you can escape ‘light blight’ (fortunately moonlight will be absent that period) and you can find a dark oasis, and know where to look, then it should be detectable to the unaided eye.

Now a word of caution, as of writing the comet is predicted to reach 4th magnitude during the 2nd and 3rd week of January, which means most people will still require a pair of binoculars to spot it due to light pollution. But you never know with comets, it may brighten even further. If you can escape ‘light blight’ (fortunately moonlight will be absent that period) and you can find a dark oasis, and know where to look, then it should be detectable to the unaided eye.

Remember comet L4 Panstarrs, which appeared in March and April of 2013? Forecast to be easily visible to the naked eye, L4 did not brighten as predicted and was just about written off as any kind of spectacle. So, when all seemed lost, the comet rallied and became quite reasonable. However most people failed to spot it. The weather didn’t help, neither did the comet’s location low in the western twilight sky – it was difficult when at its brightest.

Assuming it continues to brighten, Comet Lovejoy on the other hand will be visible high to the South for a good part of the night, allowing ample time for it to be tracked down, observed and imaged.

Comet History

Terry Lovejoy with his

Celestron 8 cope in Brisbaine

Comet Lovejoy was discovered by Australian amateur Terry Lovejoy, last August.

C/2014 Q2 turned out to be a very long-period comet, but this is not its first pass through the inner solar system. On the way in, its path showed an orbital period of roughly 11,500 years, but slight perturbations by various planets during this apparition will alter the orbit slightly, so that it will next return in about 8,000 years.

Appearance

In images the comet appears green, the glow coming from molecules of diatomic carbon (C2) fluorescing in ultraviolet sunlight in the vacuum of space.

By contrast, the comet's ion tail (gas tail) is much narrower and points directly away from the Sun, and is tinted blue. The ion tail's colour comes from fluorescing carbon monoxide ions (CO+). If comet Lovejoy had been producing more dust (as really memorable great comets do) it would have appeared whiter in hue, the dust particles simply reflecting sunlight.

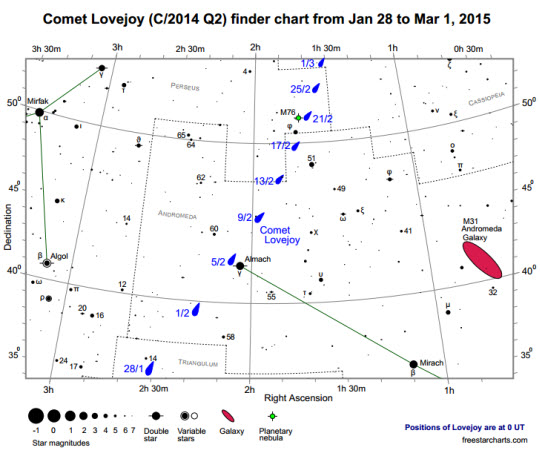

How to find Comet Lovejoy

Wait until after Jan 7th when moonlight is waning. On that day the comet will pass closest to Earth: at a distance of 0.47au (44 million miles/70 million km); and the comet will be in Northernmost Eridanus, west of Orion. As the comet reaches its brightest, this coincides with the favourable ‘dark sky window’ of opportunity, by which time the comet is crossing through Taurus and Aries high in the early evening sky. It then passes 8° West-Southwest of the Pleiades on the evening of January 17th.

The comet doesn't reach perihelion until January 30th, at a rather distant 1.29 a.u. from the Sun. By that date the comet should finally be starting to fade slightly from Earth's point of view, and by late January the Moon returns.

On the charts the position of the comet is marked every 2 days [mm/dd magnitude]. Magnitude estimates may be 1-1.5 magnitudes brighter (lower) than indicated.

|

|

| Climbing past Orion up to 17-Jan-2015 |

Climbing past Perseus |

If conditions are favourable we shall endeavour to image the comet using the Cook refractor. At very least it should be apparent as fuzzy grey blob.

Image Credits

- Comet C/2014Q Lovejoy (top image): unknown

- Comet Lovejoy+M79 Galaxy: Chris Schur of Arizona

- Finder charts: Created using Cartes du Ceil (Sky Charts) from Bob Moler's blog

In this month's Sky Notes:

Planetary Skylights

Let us first have a look in the evening twilight sky where brilliant Venus (you cannot mistake it low down above the SW horizon) has close encounters with both Neptune and Mars during February.

The one with Neptune (left) occurs on the 1st and will be best chance to spot the outer gas world before it is lost in glare. With Venus (right) at Magnitude -3.8 and Neptune at +8, the brightness difference is rather large, to say the least. Neptune will appear as a tiny blue-grey fuzz point through binoculars ¾ of a degree upper right of Venus. View around 5:45pm in the SW.

The one with Neptune (left) occurs on the 1st and will be best chance to spot the outer gas world before it is lost in glare. With Venus (right) at Magnitude -3.8 and Neptune at +8, the brightness difference is rather large, to say the least. Neptune will appear as a tiny blue-grey fuzz point through binoculars ¾ of a degree upper right of Venus. View around 5:45pm in the SW.

Then on the 21st Venus and Mars are separated by less than a degree with Mars to the upper right again. Mars will be at mag +1.2, readily visible to the naked eye. View around 6:30pm. A slim crescent moon joins the party on the 20th and 21st.

Then on the 21st Venus and Mars are separated by less than a degree with Mars to the upper right again. Mars will be at mag +1.2, readily visible to the naked eye. View around 6:30pm. A slim crescent moon joins the party on the 20th and 21st.

While  Venus may be conspicuous for the early part of the evening Jupiter (left), rules the night sky, coming to opposition on Feb. 6th and dominating the eastern aspect before 11pm. By midnight Jupiter will lie due south, ahead of the sickle asterism in Leo and therefore not far from its chief star, Regulus, although from the 4th Jupiter actually lies in Cancer. Jupiter offers up a wealth of detail when viewed through a scope, the dance of the galilean moons from day to day being particularly fascinating to follow. The moon lies nearby on the 3rd.

Venus may be conspicuous for the early part of the evening Jupiter (left), rules the night sky, coming to opposition on Feb. 6th and dominating the eastern aspect before 11pm. By midnight Jupiter will lie due south, ahead of the sickle asterism in Leo and therefore not far from its chief star, Regulus, although from the 4th Jupiter actually lies in Cancer. Jupiter offers up a wealth of detail when viewed through a scope, the dance of the galilean moons from day to day being particularly fascinating to follow. The moon lies nearby on the 3rd.

Saturn is visible in the dawn sky. Look for it after 5am when it lies low to the ESE a hand span above the horizon. The moon lies nearby on the 13th.

Saturn is visible in the dawn sky. Look for it after 5am when it lies low to the ESE a hand span above the horizon. The moon lies nearby on the 13th.

Meteor Activity

The minor Alpha Aurigids meteor shower peaks from Feb 6 - 9th. Rates are barely on a par with sporadic levels (4-6), but if you do happen to spot a shooting star heading away from the direction of the zenith, (overhead) where Auriga resides at this time of year, it is likely to be an Aurigid!

Comet Lovejoy 2014

Impressive photo of Comet

C/2014Q2 Lovejoy by Les,

who Mark met while working in

the Magpie Café. Taken with a

camera on a motorised mount.

(Click image for full view)

The weather hasn’t been kind over the ‘dark window’ period in which comet Lovejoy has been readily visible. It’s not that it has been totally cloudy, just cloudy at the wrong times, Spells of strong gusty winds and then mist and frost have all contributed to making observations a little tricky and very frustrating.

The comet reached 4th magnitude and is still below 5th magnitude as it continues to track across the sky heading to the right of Perseus and into Andromeda. Despite the difficulties with the British weather, Keith and Mark have managed to capture some images of the comet. Keith managed to capture the comet's coma through the Cooke refractor at the Bruce Observatory. Several timed images were attempted with the scope tracking the comet. Although little detail is revealed the results clearly show the comets greenish head.

Mark took some timed exposures just on a tripod, (the comet is just about visible as a green dash). Unfortunately moonlight is going to interfere for the first 9 days in February and further imaging will be hampered. Throughout the middle part of January the comet was easily seen in binoculars, appearing as a grey- green blob. It should still be apparent during the February, so please do try to spot it if not already done so.

Mark further reports that on the 24th of Jan under clear, dark skies a definite tail could be made out through binoculars.

Here are some Members' photos of the comet:

February 2015 Sky Charts

Click each image to see a full-size Sky Chart:

|

|

| Looking South Mid February - 21:15h |

Looking North |

|

|

| Looking East Mid February - 21:15h |

Looking West Mid February - 21:15h |

|

|

| Overview Mid-February - 21:15h |

Image Credits:

- Planets and Comets where not otherwise mentioned: NASA

- Sky Charts: Stellarium Software

In-Focus

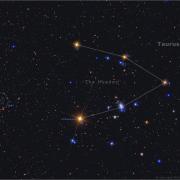

In this month's In-Focus article, Mark Dawson takes a tour of the "Heavenly G", which links bright stars in the southern winter sky.

Stellar evolution is regarded as one of the fundamental processes involved in the building of the universe we see around us today. Just as someone who studies the variety and growth of trees in a forest to fathom its evolutionary cycle, so astronomers study the forest of stars in the night sky to understand stellar cycles and the implication these have on the wider universe.

Nowhere is the life story of a star better followed than in the region bounded by the glittering array of bright luminaries sometimes referred to as the Celestial or Heavenly G, which encompasses much of the southern aspect of the winter sky. This huge asterism spans six constellations and resembles the outline of a capital G, slightly distorted and tilted. The eight bright stars that form the ‘G’ start with Aldeberan, then track up to Capella in Auriga before passing through Castor and Pollux in Gemini en route to Procyon and Sirius in the lesser and greater dogs. From Sirius the next leg takes in Rigel, before making the final dash to Betelguese in Orion.

Embedded within our snapshot of stellar life, below the belt stars of Orion, lies the Orion nebula, a stellar nursery 1250 light years distant. It is only visible because of the group of very young, hot, massive stars collectively known as the ‘Trapezium’ are illuminating it from within. Intense radiation from these stars has opened up great voids in the surrounding gas and dust clouds. Many less massive stars are also forming, cocooned in dense knots of the hydrogen gas.

The Hubble Space Telescope has uncovered over a hundred of these protostars similar in mass to our Sun. Over time stars that form in such clusters will disperse completely. The lovely open cluster in Taurus known as the Pleiades or Seven Sisters is a fine example of an open cluster, estimated to be no more than 100 million years old.

To continue our analogy with a forest of trees, stars also evolve into different types and grow to differing sizes. The chief factor in determining the paths taken come down to the initial amount of gas (and some dust) the star is formed from. Huge quantities of hydrogen gas and dust are required to make a star. Our galaxy (like many spiral galaxies) has an abundance of such material which forms in clouds tens or even hundreds of light years in size. The Orion nebula is part of one such cloud. The initial mass from a collapsing gas cloud determines the evolutionary path of a star and hence its ultimate fate. The greater the quantity of hydrogen gas being compressed and heated, the more massive a star may become, but the shorter its lifespan will be, using its fuel at a much faster rate. Take a look at blue/white Rigel in our ‘G’ for example. This brilliant star marking Orion’s foot lies around 1000 light years away but is still ranked seventh in the night sky. Rigel is young, hot and exceedingly massive, around 70,000 times more luminous than our sun. It is converting hydrogen – (its main fuel source –like all stars) at such a prodigious rate, its days are already numbered and it will shine for a few hundred million years only.

Other ‘younger’ stars on the celestial ‘G’, include Sirius, brightest star in the night sky. A mere 26 times more luminous than the Sun, Sirius is a white main sequence star with a surface temperature of around 10,000 degrees Centigrade, double that of our Sun, but only half that of Rigel. The reason Sirius appears so bright in the night sky is its proximity – just 8.6 light years distant. Sirius has a tiny companion star in attendance – a white dwarf star (known as the Pup) 24,000 miles in diameter, the degenerate core of a solar mass sized star. As to why it is so close to the Dog Star remains a bit of a mystery.

Slightly cooler than Sirius, at around 7,500 C, Procyon in Canis Minor is only seven times more luminous than our sun and situated 11.7 light years away. Like Sirius, Procyon also travels through space with a tiny companion white dwarf star. Another ‘G’ member, Castor, the northern twin of Gemini, is also of similar spectral type to Sirius (hot and white) However ‘Castor’ is really a complex sextuplet, six stars;- three sets of doubles all gravitationally bound together and located at a distance of 46 light years. Only the two main components can be separated using a modest scope.

One star of the ‘G’ that may be considered a larger version of our own sun is Capella, located high overhead in the constellation of Auriga. Although appearing as a solitary star, Capella actually consists of two stars; a binary system approximately 43 light years away. The two components are separated by just 70 million miles and can only be split in the largest of scopes. Both components are somewhat bigger, slightly more luminous, but of similar surface temperature. Like our Sun they have reached stable middle age.

Gemini’s other ‘twin’ star, Pollux resides around 36 light years distant. It is further down the evolutionary path, but still regarded as being on the main sequence. Being a little more massive it is converting fuel at a slightly faster rate than our sun. Physically larger, Pollux has a cooler surface temperature as it begins to expand, a fact borne out by the deep amber hue it exhibits when viewed with optical aid and in comparison to Castor, its twin.

Ageing stars nearing the final stages of their lives appear orange in colour. Undergoing a series of internal physical changes, the eventual fate of the remaining two stars of the celestial ‘G is however very different. Aldebaran, appears to be the brightest member of the “V” shaped Hyades open cluster marking the bull’s head, but it lies at half the distance of the genuine cluster members which are 120 light years away. This ‘fiery eye’ has swelled to become a giant star some 35 million miles in diameter. Its eventual demise will be relatively gentle, ‘coughing’ into space most of its bulk, the outer layers becoming intricate bubbles and rings. Along with the vast majority of stars of a similar initial mass to our Sun, Aldebaran will end its days as a planetary nebulae, at the heart of which feebly shine the star’s exposed and extremely dense core, known as a White Dwarf, perhaps 20-30 thousands of miles in diameter.

The most conspicuous orange star of the ‘G’ asterism is Betelguese marking Orion’s shoulder. This red supergiant is so large (and relatively close) its disk has actually been imaged by the Hubble Space Telescope, estimated to be around 500 million miles in diameter at maximum. Betelgeuse constantly readjusts its internal structure to maintain stability, expanding and contracting, thus appearing slightly variable in brightness. One day (hopefully soon - 10000yrs) the fuel supply at the core will be exhausted and nuclear reactions will shut down, ending the force of radiation outwards. With equilibrium lost, the force of gravity will take charge and the outer layers of Betelgeuse will start to collapse onto the core, being hit as they do so by a wave of neutrinos going the other way and causing detonation – Bang. Then, for perhaps 8 weeks Betelgeuse will rival the moon in brightness, before finally fading into obscurity, leaving behind an expanding nebulous maelstrom of gas and a tiny super dense core perhaps 20 miles across known as a neutron star.

If you have access to a telescope, evidence of one such cataclysmic event may be glimpsed in the constellation of Taurus, just above zeta tauri, the star marking the southern horn. Noted by Chinese astronomers as a brilliant ‘guest star’, this supernova blazed forth in 1054 rivalling the quarter phase moon for several weeks. The remnant is known today as the Crab nebula (M1). Viewed through a typical backyard scope the nebula appears as a faint milky stain, but large scopes reveal the expanding and intricate shock waves racing outwards into space and away from its rotating neutron core, a pulsar. Should the shockwaves encounter a region of dense interstellar cloud; like the Orion cloud, a wave of new stellar formation may commence, setting in motion a new stellar cycle. This then is the legacy, the final parting gift, of massive stars, seeding space with the elements necessary for life to arise, and given the breaks, for complex life to potentially thrive. The evidence is overwhelming and compelling, whether it’s the calcium in your bones, the iron in your blood, or even the gold or silver band around your finger, just like you and me it’s all star stuff!

Events

Observe the night sky with us at the Bruce Observatory, Whitby School

Observe the night sky with us at the Bruce Observatory, Whitby School

Observing Nights are held weather permitting: check for a relatively clear sky before leaving home. If in doubt, Mark can be reached on 07886069339

Please note the college drive gate is now operated via a electronic key code - so anyone wishing to attend must be at the car park at the top of the drive by 19:00hrs - unless an arrival time has been arranged with Mark/Keith.

Whitby Youth Hostel - East Whitby - rear of Abbey vistor centre.

Whitby Youth Hostel - East Whitby - rear of Abbey vistor centre.

Observe the night sky with us at the Bruce Observatory, Whitby School

Observe the night sky with us at the Bruce Observatory, Whitby School

Observing Nights are held weather permitting: check for a relatively clear sky before leaving home. If in doubt, Mark can be reached on 07886069339

Please note the college drive gate is now operated via a electronic key code - so anyone wishing to attend must be at the car park at the top of the drive by 19:00hrs - unless an arrival time has been arranged with Mark/Keith.

Whitby School, Prospect Hill site, Main block, Room H1 (first along corridor from Hall).

In our monthly meetings, we review the night sky for the upcoming month using a Planetarium program, have talks and presentations on astronomy and space topics, and discuss future events. New members are welcome.