In this month's Sky Notes:

- Planetary Skylights.

- March Meteors.

- Solar and Lunar Eclipses.

- The Spring Eqinox.

- March night Sky.

- The Messier Marathon.

- March 2025 Sky Charts.

Planetary Skylights - Brief

Venus is prominent but quickly descends in the evening sky, Jupiter is visible until early morning, and Mars follows. Mercury completes a favourable evening appearance, while Uranus moves westward.

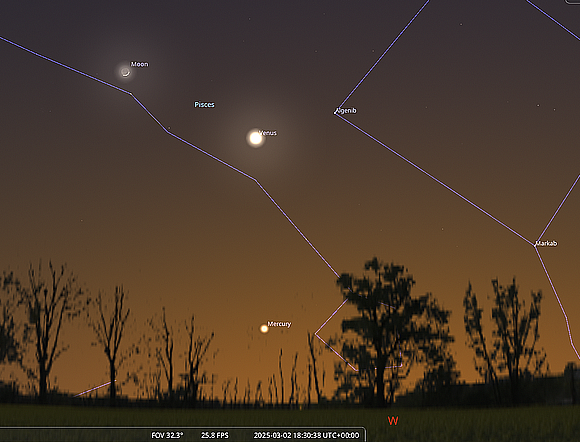

Venus starts the month 23+ degrees above the west horizon but will quickly drop back toward it, disappearing into twilight by the 21st. By then, it will be just a 2% crescent, 60 arcseconds in diameter, and only 41 million km from Earth. For the best view, observe Venus in twilight to reduce glare from its -4.2-magnitude brightness. The crescent Moon lies below Venus on March 1st and above it the next evening.

Venus starts the month 23+ degrees above the west horizon but will quickly drop back toward it, disappearing into twilight by the 21st. By then, it will be just a 2% crescent, 60 arcseconds in diameter, and only 41 million km from Earth. For the best view, observe Venus in twilight to reduce glare from its -4.2-magnitude brightness. The crescent Moon lies below Venus on March 1st and above it the next evening.

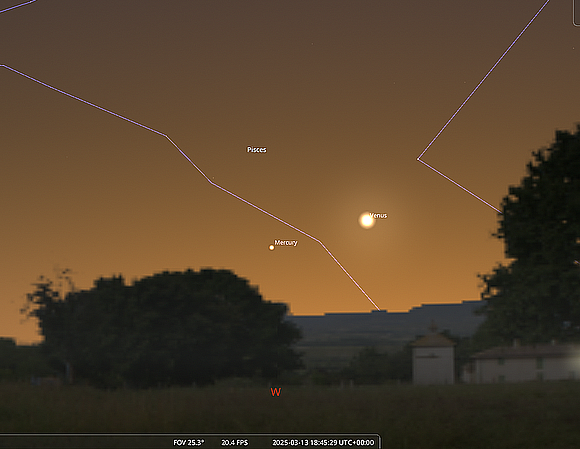

March 1st - 18:15hrs GMT. Moon with Venus above and Mercury below in evening twilight.

(Click for full image)

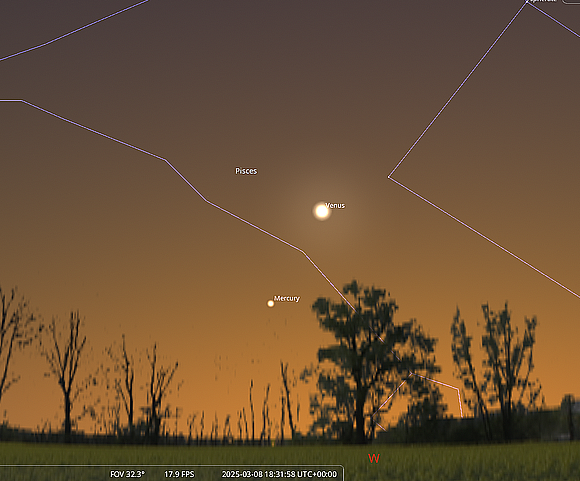

Mercury continues its most favourable evening apparition of the year into March, visible above the west horizon by 18:30hrs GMT. At the beginning of the month Mercury will be almost magnitude -1, but the low altitude will temper this somewhat to around -0.55, still bright enough to be seen with the naked eye if you have a flat western horizon.

Mercury continues its most favourable evening apparition of the year into March, visible above the west horizon by 18:30hrs GMT. At the beginning of the month Mercury will be almost magnitude -1, but the low altitude will temper this somewhat to around -0.55, still bright enough to be seen with the naked eye if you have a flat western horizon.

On March 1st, look for Mercury about 8 degrees above the horizon, below a young crescent Moon with Venus shining brightly above. Use binoculars if you have difficulty spotting Mercury. The whole scene will be picture perfect for imaging.

Mercury will reach its greatest eastern elongation of 18 degrees from the Sun by March 8th. Although it will be slightly fainter at a magnitude of -0.2, it will still be over 10 degrees above the horizon by the end of civil twilight. When observed through a telescope, Mercury appears very small and shows limited detail, except for its phase changes as an inferior planet (located inside Earth's orbit). In early March, the phase of Mercury is approximately 73% gibbous, decreasing to a 44% crescent by the 10th. To observe these details, use medium to high magnifications and consider employing an orange or light-red filter to enhance surface detail visibility. As the month progresses, Mercury will gradually move back towards the western horizon, fading in brightness, and will pass through inferior conjunction with the Sun on the 24th.

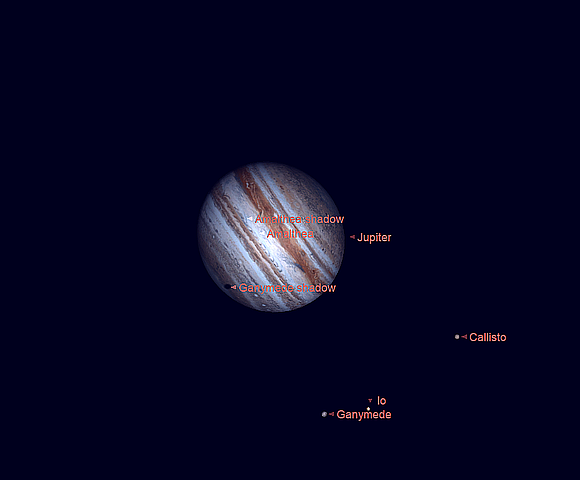

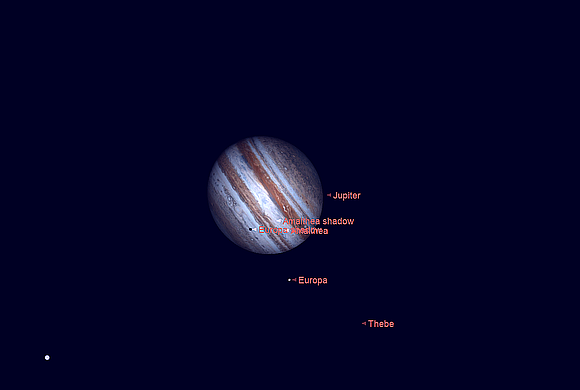

Jupiter remains conspicuous in the night sky, moving west with the stars of Taurus. Jupiter’s observing window diminishes to around 6 hours by the end of March by which point British Summer Time (BST) is in operation, still plenty of time to scrutinise Jupiter and its satellite family. At over 60 degrees high, Jupiter's brightness slightly decreases from -2.5 to -2.3 magnitude. On March 5th, a crescent Moon lies near Jupiter.

Jupiter remains conspicuous in the night sky, moving west with the stars of Taurus. Jupiter’s observing window diminishes to around 6 hours by the end of March by which point British Summer Time (BST) is in operation, still plenty of time to scrutinise Jupiter and its satellite family. At over 60 degrees high, Jupiter's brightness slightly decreases from -2.5 to -2.3 magnitude. On March 5th, a crescent Moon lies near Jupiter.

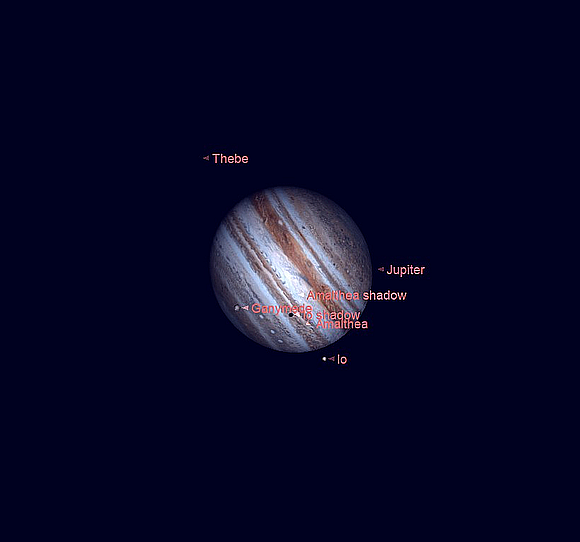

For the better part of March Jupiter continues to be a fine spectacle in the eyepiece, although it will be descending into more unstable 'seeing' air by the end. The dark equatorial belts across the oblate disk, along with the Galilean moons, can be seen using instruments with an aperture as small as 60mm (2.6”), including mounted binoculars

Larger telescopes may reveal additional details such as the Great Red Spot, a vast storm system that has decreased in size and intensity over the past three decades. The GRS can be seen with 100mm (4”) telescopes but is more prominent with 150mm (6”) instruments at medium magnification. Optimal dates to observe the GRS are March 2nd, 5th, 7th, 9th, 12th, 14th, 16th, 21st, 26th, 28th, and 31st between 19:00hrs and 20:30hrs GMT.

The dynamic orbits of Jupiter's Galilean moons offer a fascinating spectacle from night to night, especially when shadow transits are visible. Key March events include Io on March 2nd at 19:30 and March 25th at 20:00, Europa on March 28th at 20:00, and Ganymede on March 18th at 19:45 GMT. A 100mm aperture with high magnifiction should be adequate, but 150mm (6") instruments would be more suitable.

Mars remains a bright object in the night sky, its rusty hue conspicuous in the heart of Gemini. Its magnitude will drop from -0.25 to +0.5 by the months end. After being almost stationary, Mars resumes direct of prograde motion after mid-month back toward the Twins lead stars Castor and Pollux. At the start of the March Mars exhibits an 11 arc-second disk reducing to 8.5 arc-seconds by the months end, so it will appear rather small in the eyepiece. Surface features will therefore become increasingly difficult to resolve in more modest telescopes. The quarter Moon resides upper right of Mars on March 8th.

Mars remains a bright object in the night sky, its rusty hue conspicuous in the heart of Gemini. Its magnitude will drop from -0.25 to +0.5 by the months end. After being almost stationary, Mars resumes direct of prograde motion after mid-month back toward the Twins lead stars Castor and Pollux. At the start of the March Mars exhibits an 11 arc-second disk reducing to 8.5 arc-seconds by the months end, so it will appear rather small in the eyepiece. Surface features will therefore become increasingly difficult to resolve in more modest telescopes. The quarter Moon resides upper right of Mars on March 8th.

Uranus remains an observable telescopic object throughout March, positioned near the faint stars in southern Aries, 7.5 degrees lower right of the Pleiades star cluster. While it is on the verge of being visible to the naked eye, Uranus typically requires binoculars to be identified as a magnitude +5.8 'faint star.' Telescopes with apertures of 80mm (3") or larger are needed to reveal its small, 3.7 arc-second grey-green disk. Instruments with apertures of 150mm (6") or more provide a clearer resolution. The magnitude +4.4-star Delta Arietis, also known as Botein, is the nearest 'naked eye star,' located 3 degrees to the right of Uranus.

Uranus remains an observable telescopic object throughout March, positioned near the faint stars in southern Aries, 7.5 degrees lower right of the Pleiades star cluster. While it is on the verge of being visible to the naked eye, Uranus typically requires binoculars to be identified as a magnitude +5.8 'faint star.' Telescopes with apertures of 80mm (3") or larger are needed to reveal its small, 3.7 arc-second grey-green disk. Instruments with apertures of 150mm (6") or more provide a clearer resolution. The magnitude +4.4-star Delta Arietis, also known as Botein, is the nearest 'naked eye star,' located 3 degrees to the right of Uranus.

March Meteors.

March continues where February left off with no recognised meteor showers of note, but those sporadic meteors that are spotted are often brighter than average examples. It has been suggested that late January to early March; the 'fireball' season', may be a very old, depleted shower of similar nature to the Geminids. Towards the end of March there are signs of activity from the various and complex Virginid radiants, but numbers remain low with 'peak activity' not reached until April. The main radiants lie near Spica and Kappa Virginis, but typically just a few meteors per hour are recorded by an observer. True Virginids are often slow moving and long in duration, occasionally very bright (Jupiter brightness) producing flares along their path.

Solar and Lunar Eclipses Visible

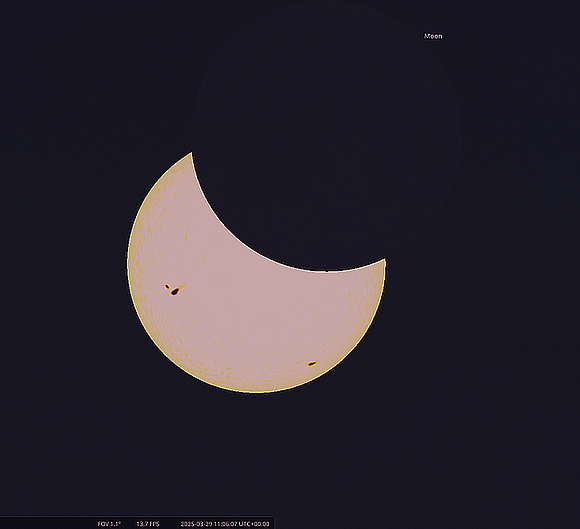

During March, two eclipses will be visible: one lunar and one solar. The total lunar eclipse on the 14th will not reach totality in the UK until after the Moon has set. The partial solar eclipse on March 29th will be more observable.

The lunar eclipse in the early hours of March 14th requires an early start for those who wish to observe it. Setting an alarm for 05:00 will allow observers to see the Earth's umbral shadow cutting into the southwest quadrant of the Moon by 05:20. The Moon will be low in the western sky at this time.

As the Moon sets towards the western horizon, the Earth's shadow will continue to move slowly across the full Moon, almost reaching totality. However, for UK observers, the Moon will set around 06:10hrs GMT before this occurs. Additionally, a second total lunar eclipse later this year will also not be visible from the UK.

The lunar eclipse shortly before the Moon drops below the west horizon around 06:10hrs.

The lunar eclipse shortly before the Moon drops below the west horizon around 06:10hrs.

(Click for full image)

A partial solar eclipse will be visible from the UK on the morning of March 29th. Maximum obscurity will vary, with the western regions more favoured. In Whitby, the eclipse will reach almost 36%. The lunar limb will first contact around 10:10 GMT.

The lunar limb will obscure the upper right-hand side of the Sun, gradually covering the top of the solar disk. By 10:45hrs, a significant portion will be obscured.

Maximum obscurity is around 11:06 AM, covering about 36%.

The eclipse ends shortly after midday, with the Moon leaving the Sun at 12:10 PM.

Use eclipse glasses (check for holes) to view the eclipse safely with the naked eye. A high-number welder's glass can also be used briefly. For telescopes or binoculars, either project the image onto a shaded white card or use an appropriate solar filter over the aperture. Filters can be neutral density, glass, Mylar, Baader solar film, or similar. Always inspect filters for holes, tears, and proper fit. Never look directly at the Sun to avoid eye damage.

The Spring Equinox

Spring bursts forth! Hole of Horcum - North York Moors. Image - M Dawson

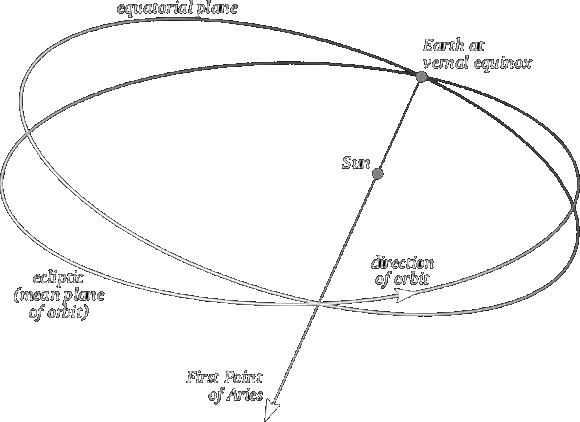

The date of the Spring or Vernal Equinox, marking the start of astronomical spring in the northern hemisphere, falls on March 20th this year. The Vernal Equinox represents a specific moment when the Sun's path on the ecliptic crosses the celestial equator as it appears to move northwards in the sky for the northern hemisphere.

During the spring or autumnal equinox, the Earth's orientation is such that neither pole is inclined toward the Sun, resulting in nearly equal hours of daylight and darkness for all locations. This term, equinox, comes from Latin meaning "equal night". However, it is not entirely accurate that both day and night are exactly 12 hours long on this date, as daylight is still slightly longer. The actual date where daylight and darkness are equal, known as the equilux, occurs a few days before the spring equinox.

As Spring begins, the length of day increases significantly in most areas, except for the tropics, where day lengths remain relatively constant throughout the year. The greatest increase occurs around the spring equinox. Afterward, days continue to lengthen but at a decreasing rate. On the longest day of the year, the summer solstice, this daily difference becomes zero. Locations farther from the equator experience larger day-to-day changes. For example, in Whitby, the day of the spring equinox is 3 minutes longer than the previous day; in Athens, approximately 2000 kilometres or 1200 miles farther south, the difference is about 90 seconds. The Vernal Equinox is also known as the 'First point of Aries', named because the Sun used to be in front of the constellation Aries when it crossed the celestial equator. Although still called the 'first point of Aries', its position is now in Pisces due to precession, which is the Earth's slow wobble.

For thousands of years, people have observed that certain star patterns rise just before the Sun at specific times and considered this significant. They mapped the apparent path of the Sun against these constellations, known as the Ecliptic. The broader zone along which planets travel is called the Zodiac, named for the 12 constellations associated with living creatures. The zodiac constellations extend about 8° north and south of the ecliptic. The origins of the zodiac signs date back to Babylonian astronomy around 1500 BC, which evolved into modern astrology. The Babylonians chose 12 zodiac signs, excluding Ophiuchus.

The Ecliptic and Zodiac constellations arranged around the celestial sphere.

Zodiac literally means 'circle of little animals'. Libra was once considered part of Scorpius, specifically its claws. Ophiuchus, the serpent-bearer, immediately following Scorpius, was originally regarded as a zodiac group. When the stars of Libra were given their own status, Ophiuchus was no longer included in the zodiac, which simplified matters for astrologers. For those who have difficulty remembering the order of the zodiac constellations, the following rhyme may be useful.

The Ram, the Bull, the Heavenly twins and next the Crab the Lion shines, the Virgin, and the Scales.

Scorpion, Archer and Sea goat, The man who pours the water out and Fish with glittering tails.

March Night Sky

March is considered one of the optimal months for observing the night sky, particularly for residents of the Northern Hemisphere, including those in the UK. This month signifies significant changes, as it encompasses the beginning of Spring with both meteorological (March 1st) and astronomical (March 20th or 21st) dates. The latter date also marks the Vernal or Spring Equinox. Additionally, in the UK, March heralds the transition to British Summer Time (BST), with clocks advancing by one hour on March 30th this year. While thoughts may turn to spring, the weather can remain harsh, with cold, wet, and occasionally snowy conditions.

March is frequently regarded by amateur astronomers as an optimal period for observing the night sky. During this month, the hours of darkness surpass daylight hours until near its conclusion, making evenings more conducive to extended observation sessions. Additionally, Earth's position in its orbit around the Sun allows for the viewing of constellations and deep sky objects associated with all four seasons throughout the course of a single night. Moreover, if moonlight is absent, there exists the possibility of undertaking an extensive celestial observation marathon, the Messier Marathon

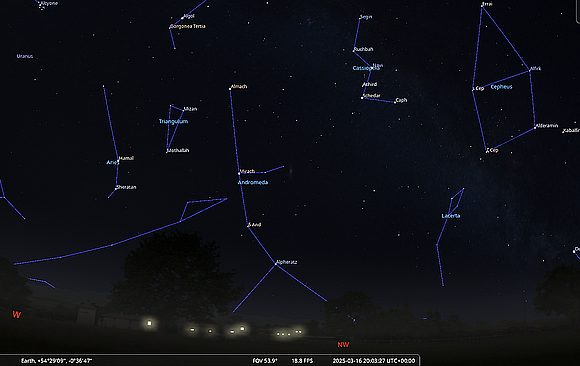

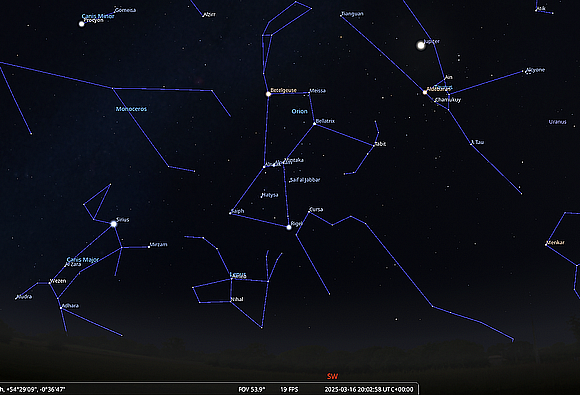

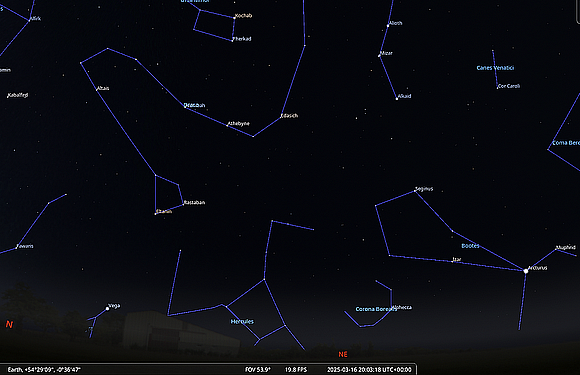

The gradual progression of the March sky remains relatively stable until the final day of the month, which coincides with the commencement of British Summer Time (BST). Prior to this transition, early March provides reasonable visibility of certain autumnal constellations. In the west-northwest (WNW) direction, one can observe the Great Square of Pegasus, with the stars of Andromeda extending upwards from the horizon towards the figures of Perseus and Cassiopeia, which flank the zenith directly overhead. Circumpolar summer stars are relegated to the celestial margins, low in the northern sky, where Vega in Lyra and Deneb in Cygnus subtly interact with the horizon.

The well-known Plough (or Big Dipper) asterism in Ursa Major stands vertically to the northeast. The 'pointer stars'—Dubhe and Merak, located at the rear of the bowl—are used to locate Polaris, the Pole Star in Ursa Minor. The celestial dragon, Draco, winds its way between these two constellations, with its head marked by an irregular quadrilateral of stars situated due north and not far from Vega.

Early in March as twilight deepens, overhead the distinctive 'W' pattern of Queen Cassiopeia first occupies the zenith. This is followed by Perseus, whose outline resembles a distorted Pi symbol, and then the stars of Auriga the Charioteer, highlighted by the brilliant Capella, which is a circumpolar winter star from this latitude.

High to the southwest, the 'V' pattern of the Hyades star cluster marks the head of Taurus, pointing down to the northwest horizon. Among the cluster's stars, Aldebaran, the conspicuous 'eye of the bull' with its marmalade hue, masquerades as a true member but resides at half the distance of genuine cluster members, being approximately 65 light-years closer. To the west of the Hyades, the beautiful Pleiades star cluster, or Seven Sisters, continues to flee from the advances of Orion, the mighty hunter who strides into the western half of the sky, accompanied by the sparkling tableau of winter.

Orion can be identified by its three belt stars, as well as the first-magnitude luminaries Rigel and Betelgeuse. These stars are at opposite ends of their life cycles but are both destined to go supernova. Betelgeuse, a red supergiant, is nearing the end of its life, potentially thousands of years hence, while white Rigel still has millions of years remaining—a mere blink of the cosmic eye.

Situated beneath the belt stars lies one of the prominent objects in the night sky, the Orion Nebula. This region of stellar birth is approximately 1300 light-years away and around 2.4 million years old. It comprises a vast cloud of gas and dust extending 25-35 light-years across, where star formation is actively occurring. The nebula hosts the richest star cluster within our galactic vicinity, although many stars remain obscured. While the nebula appears as a misty spot through small binoculars, it can be breathtaking when observed through a telescope. Observers should look for the Trapezium star cluster, featuring four notable stars that are visible even with smaller telescopes.

Orion's two hunting dogs, Canis Major and Canis Minor, follow their master across the sky. The belt stars of Orion point towards Canis Major and Sirius, the brightest night star, which is visible due south at nightfall. Above and to the left is Procyon, another notable winter star in the lesser dog Canis Minor. The brightness of both stars is due to their proximity to Earth, being 8.6 and 11 light-years away respectively. Both stars have companion white dwarf stars that are challenging to observe even with large instruments.

The Winter Milky Way flows up beside Orion, separating the two dogs. Below Orion's feet, above the SSW horizon, lies the celestial hare Lepus. To the left of Orion is the modern constellation Monoceros, the Unicorn. Its stars are faint, but the area contains numerous star clusters and nebulae that are not visible to the naked eye. Below the Unicorn, Puppis, part of the defunct constellation Argo Navis, straddles the southern horizon and contains several rich galactic clusters and nebulae, including Messier objects M46, M47, and M93.

Eridanus, the longest constellation in the sky, occupies much of the area lower right of Orion. The river Eridanus starts near Rigel, marked by Cursa (Beta Eridani), and flows parallel to the southern horizon before descending into the southern hemisphere, ending at the brilliant star Achernar. To the upper left of Orion, one can observe the Twins of Gemini, distinguished by the two stars, Castor and Pollux. Castor, situated further north, is slightly dimmer than its twin Pollux, which emits a pale amber glow. While Castor appears solitary to the unaided eye and through binoculars, it is a sextuplet system, with the brightest two components separable in modest telescopes under stable atmospheric conditions.

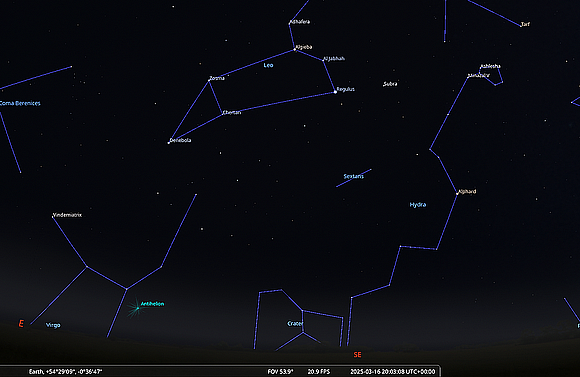

As March advances, the winter constellations gradually move westward, giving way to a collection of spring constellations that grace the celestial stage. The unremarkable stars of Cancer follow Gemini and signify the transition between seasons. Although faint, Cancer encompasses the splendid open cluster M44, also known as the Beehive Cluster or Praesepe. The most prominent constellation of spring, Leo the Lion, follows next, identifiable by the distinctive 'Sickle' asterism, at the base of which lies bright Regulus, positioned near the ecliptic.

Ahead of Regulus and below Procyon, a faint but distinct 'knot' of stars marks the head of Hydra, the largest constellation by area in the night sky. Hydra's isolated chief star, Alphard—known as the 'Lonely one'—is located just below this head, recognizable by its amber hue and relative brightness. As the month progresses towards midnight, the entirety of Hydra becomes visible, accompanied by two constellations resting on its coils: Crater the Cup and Corvus the Crow. Finally, As you look towards the east, you will notice the brilliant amber hue of Arcturus in the constellation Boötes, the Herdsman. It is the second brightest star visible from the UK after Sirius. The soft orange glow of Arcturus contrasts distinctly with the sparkling appearance of Sirius.

By the end of March, Spica, the primary star in the constellation Virgo, reappears in our skies after being below the horizon for almost six months. As the symbol of crop sowing, Spica joins the constellations associated with Hercules, gradually replacing the stars linked to the long, dark nights of winter as spring firmly establishes itself in the night sky.

The Messier Marathon

If the night skies are clear during the latter half of March, particularly around the Spring equinox, astronomers may consider undertaking an observational challenge—a race against time known as the Messier marathon. This endeavour involves identifying as many objects catalogued by the renowned French astronomer Charles Messier, the leading comet discoverer of the mid-18th century, between sunset and the following sunrise. Many amateur astronomers in the Northern Hemisphere attempt this challenge, though few complete it successfully. From UK latitudes and mid-northern Europe, it is not possible to observe all the objects, but observers can still strive for personal bests.

Over the years, the Messier catalogue has been revised multiple times and currently lists 110 objects. These include galaxies, star clusters, nebulae, and the catalyst for Messier's work—the supernova remnant known as the Crab Nebula in Taurus (M1). For instance, the great nebula in Orion is identified as M42, the Pleiades as M45, the Andromeda galaxy as M31, and the Ring nebula as M57.

On any clear night, at least twenty Messier objects may be visible. However, due to their distribution in the sky, early spring is particularly suited for observing them. Galaxies and open star clusters are abundant throughout the winter/spring constellations visible during the first part of the night, while globular clusters and many nebulae associated with summer skies become visible before dawn. Hence, the concept of the Messier Marathon emerged—an all-night endurance race to observe as many entries as possible before sunrise. A simple pair of binoculars is sufficient to view a significant number of these objects, some of which are even visible to the naked eye.

All the entries can be observed with a 120mm reflector or refractor telescope. Therefore, with modest equipment, a sky chart or app, and basic knowledge of the night sky, even novice astronomers can identify around three dozen objects without staying up all night.

The favourable news is that in March, moonlight will be nearly absent (or at least minimal) during the latter part of the month, creating ideal conditions for deep-sky observations, provided the weather cooperates. Additionally, with clocks not moving forward in the UK until near the end of March, the conditions are doubly advantageous.

March 2025 Sky Charts

Additional Image Credits:

- Sky charts/Sky chart images credits: Stellarium and Starry Night Pro Plus 8

- Log in to post comments