In this month's Sky Notes:

Planetary Skylights - Brief

Saturn is lost to the horizon this month, Neptune following behind. Jupiter journeys' westward, Uranus is well placed for evening observation. Venus sculks in the dawn sky.

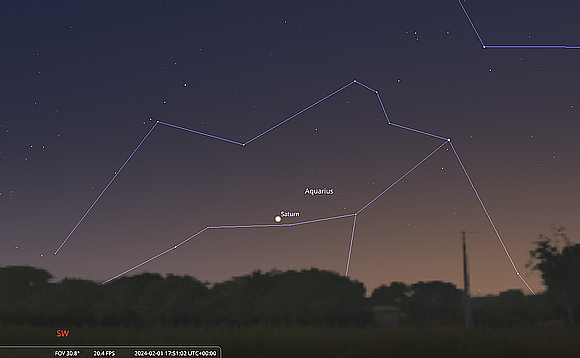

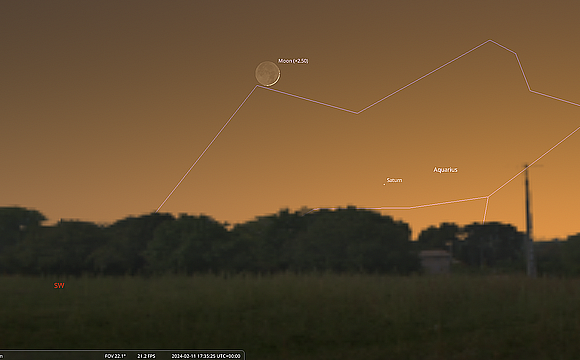

Saturn departs from UK skies shortly after mid-February, and should be considered a naked eye, or binocular object only until then. Observing with a telescope may reveal the rings (you will need to do so early, and have a flat SW horizon), but image quality will be poor. Before Saturn fades from sight in the twilight sky, try spotting it on the evening of Feb 11th lower right of a very slender crescent Moon just over 2 days old (a challenge in itself). View around 17:45hrs low in the WSW horizon, the Moon sitting just 6 degrees above it by the time it becomes noticeable, with Saturn less than half that distance lower right. Use binoculars to help pick out both objects. After mid-month Saturn will be lost, not visible again until June in very early dawn sky.

Saturn departs from UK skies shortly after mid-February, and should be considered a naked eye, or binocular object only until then. Observing with a telescope may reveal the rings (you will need to do so early, and have a flat SW horizon), but image quality will be poor. Before Saturn fades from sight in the twilight sky, try spotting it on the evening of Feb 11th lower right of a very slender crescent Moon just over 2 days old (a challenge in itself). View around 17:45hrs low in the WSW horizon, the Moon sitting just 6 degrees above it by the time it becomes noticeable, with Saturn less than half that distance lower right. Use binoculars to help pick out both objects. After mid-month Saturn will be lost, not visible again until June in very early dawn sky.

At magnitude -2.4 Jupiter by far the most conspicuous planetary presence in the evening sky and remains well placed for UK observers. As dusk falls you will find Jupiter high to the SSW at the start of February, not dropping below the horizon until after midnight (23:00hrs by the month's end). A waxing crescent Moon lies below Jupiter on February 14th.

At magnitude -2.4 Jupiter by far the most conspicuous planetary presence in the evening sky and remains well placed for UK observers. As dusk falls you will find Jupiter high to the SSW at the start of February, not dropping below the horizon until after midnight (23:00hrs by the month's end). A waxing crescent Moon lies below Jupiter on February 14th.

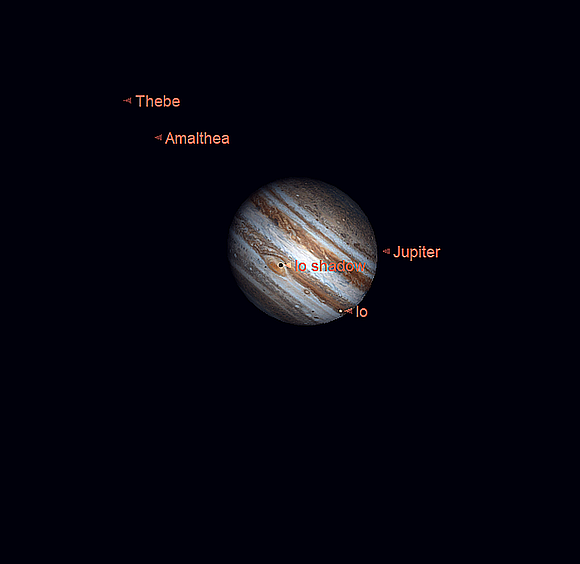

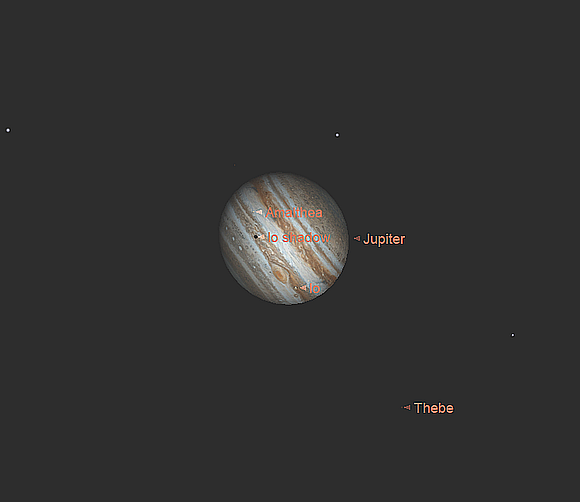

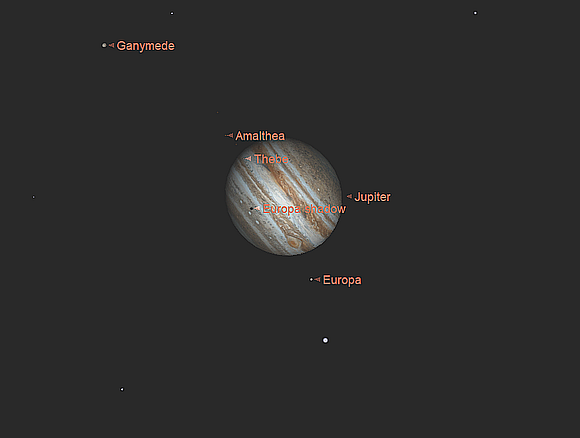

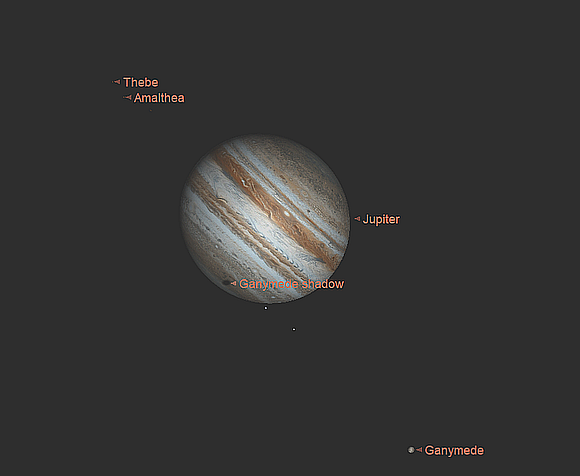

Through the eyepiece Jupiter is a wonderful sight exhibiting a disk clearly oblate some 44 arc seconds in diameter flanked by the Galilean moons, seen as specks of light. The dark equatorial belts will be readily visible in instruments as small as 60mm (2.5”) aperture, with the less evident polar regions apparent in 75mm instruments. Mounted binoculars in the range of 12 x 50 and 15 X 70 should also reveal these features. Larger instruments will show the finer northern and southern temperate belts.

When orientated in our direction look for the great red spot feature, a colossal storm system, which over the last four decades appears to have diminished in size and hue intensity. The GRS can be observed in 100mm (4”) scopes but will be more obvious with 150mm (6”) instruments at medium powers. Look for the GRS on Feb 1st, 3rd, 8th, 10th, 15th, 20th, 22nd, 25th, 27th and 29th between 19:00hrs and 21:30hrs GMT.

The Galilean moons are planetary sized worlds orbiting around Jupiter in different time periods just like a mini solar system. Regular observers of the Jovian system will be familiar with this 'dance' of Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto around Jupiter, throwing up a different configuration each night. From time-to-time shadow transits occur (visible as black dots transiting the disk of Jupiter) and are particularly fascinating to follow. To view these an aperture of 100mm (4") with high magnification should suffice. The moons themselves are far more challenging to spot in front of Jupiter, requiring much larger apertures. The most favourable evening shadow transits in February are Io - Feb 8th @ 19:45hrs & Feb 15th @ 20:30hrs. Europa - 25th @ 19:30hrs. Ganymede - Feb 4th @ 19:30hrs GMT.

Uranus remains well placed for observation in the evening sky located roughly between Jupiter and the Pleiades star cluster. With a magnitude of +5.9 Uranus is technically visible to the naked eye, however very dark, transparent skies and knowledge of the exact location are required to achieve this. An aperture of 75-80mm (3") at high power can reveal the tiny 3.5-degree disk, soft green/grey in hue, whilst instruments above 150mm (6") will clearly show it.

Uranus remains well placed for observation in the evening sky located roughly between Jupiter and the Pleiades star cluster. With a magnitude of +5.9 Uranus is technically visible to the naked eye, however very dark, transparent skies and knowledge of the exact location are required to achieve this. An aperture of 75-80mm (3") at high power can reveal the tiny 3.5-degree disk, soft green/grey in hue, whilst instruments above 150mm (6") will clearly show it.

Uranus currently resides in the lower reaches of Aries, not far above the 'head' of Cetus, but close to the Taurus/Aries border, some 53 degrees above the south horizon as dusk falls at the start of February. There are no obvious stars nearby - the 4th magnitude Delta Ari (Botein) sits just over 2 degrees above Uranus, 53 and 54 Ari are also nearby, but even fainter. The waxing quarter Moon sits 3.5 degrees to the right of Uranus on February 15th around 19:30hrs GMT.

February 15th - 19:30hrs GMT - Uranus with Quarter Moon to the side and Jupiter below.

(Click for full image)

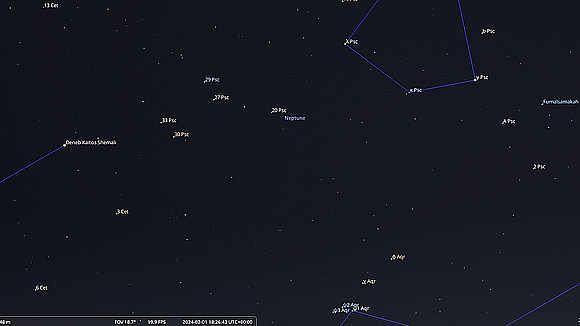

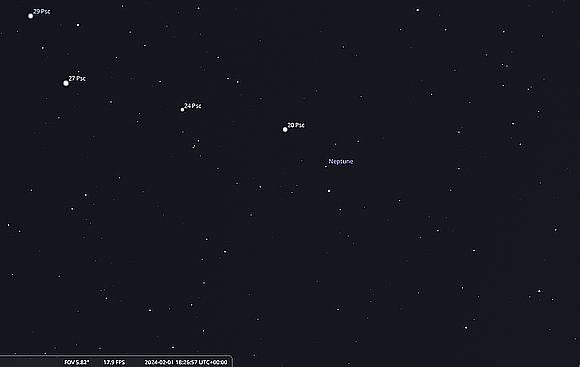

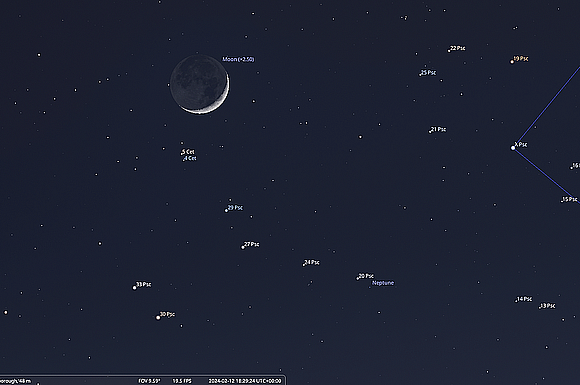

Neptune remains above the horizon throughout February although by end of the month it is perilously close as dusk falls. Neptune resides below the faint loop of stars marking the western fish of Pisces. You can locate it roughly midway, and below an imaginary line drawn from 30 Psc and lambda Piscium (mag 4.5). The nearest 'bright' star is 5th magnitude 20 Piscium 21 arcminutes to the right of Neptune. Neptune itself appears as a minute 2.4 arc-second disk of magnitude +7.9 seen through the eyepiece.

Neptune remains above the horizon throughout February although by end of the month it is perilously close as dusk falls. Neptune resides below the faint loop of stars marking the western fish of Pisces. You can locate it roughly midway, and below an imaginary line drawn from 30 Psc and lambda Piscium (mag 4.5). The nearest 'bright' star is 5th magnitude 20 Piscium 21 arcminutes to the right of Neptune. Neptune itself appears as a minute 2.4 arc-second disk of magnitude +7.9 seen through the eyepiece.

Unless 'seeing' is steady the blue/grey disk is not obvious, an aperture of 150mm (6”) and medium/high magnification is required to clearly define it. Neptune can be spotted as a speck in 10x50 binoculars (if you know exactly where to look). On February 12th a wafer crescent Moon sits 5 degrees below Neptune. By the month’s end Neptune is setting by 18:45hrs GMT from the UK.

Venus, for so long a brilliant presence in the dawn sky is nearing the end of its morning apparition, spending most of February running parallel to the SE horizon. Nevertheless, at magnitude -4.0 Venus will still appear conspicuous if the observer’s horizon is flat enough. In a dark sky Venus can appear over dazzling through the eyepiece, but as it's rising after 06:30hrs GMT as twilight grows brighter, this will less of an issue. At such low altitudes unsteady 'seeing' will be an issue, although Venus' phase should be detectable. A very slim waning crescent Moon resides well to the right of Venus on Feb 6th - view around 07:20hrs GMT. Venus is joined by Mars by less than half a degree on February 22nd, however by 07:30hrs this will be extremely challenging to view in a bright twilight sky.

Venus, for so long a brilliant presence in the dawn sky is nearing the end of its morning apparition, spending most of February running parallel to the SE horizon. Nevertheless, at magnitude -4.0 Venus will still appear conspicuous if the observer’s horizon is flat enough. In a dark sky Venus can appear over dazzling through the eyepiece, but as it's rising after 06:30hrs GMT as twilight grows brighter, this will less of an issue. At such low altitudes unsteady 'seeing' will be an issue, although Venus' phase should be detectable. A very slim waning crescent Moon resides well to the right of Venus on Feb 6th - view around 07:20hrs GMT. Venus is joined by Mars by less than half a degree on February 22nd, however by 07:30hrs this will be extremely challenging to view in a bright twilight sky.

February Meteors

There are no recognised meteor showers of note during February, the Alpha Aurigids are a very minor shower running from mid-January thru' to mid-February, however numbers are indistinguishable from sporadic levels; barely 2-5 per hour. That said, meteors witnessed at this time of year are often bright and it has been suggested that the period from late January to March; the 'fireball' season', may be a very old, depleted shower of similar nature to the Geminids, composed of more dense, rocky debris. If you do spot a meteor speeding away from Auriga, make a mental note, otherwise it's just an anonymous sporadic debris fragment.

February Night Sky

With the thought of the darkest of winter days now starting to recede as daylight is perceptibly lengthening, thoughts may be turning to the arrival of meteorological spring at the start of March - just 29 days away. This may be true, and yet the worst of winter conditions could just be around the corner with astronomical spring not commencing until the spring equinox on March 21st. One thing is for certain as you step outside into the evening air, the night sky certainly reflects astronomical mid-winter, with those constellations associated with it holding centre stage. February skies, I will argue, are at their most majestic, beckoning the observer to 'come and explore'.

At the start of the month the western aspect of the evening sky is still dominated by autumnal constellations, in particular the great square of Pegasus, with the stars of Andromeda reaching up to the figures of Perseus and Cassiopeia departing the zenith - overhead.

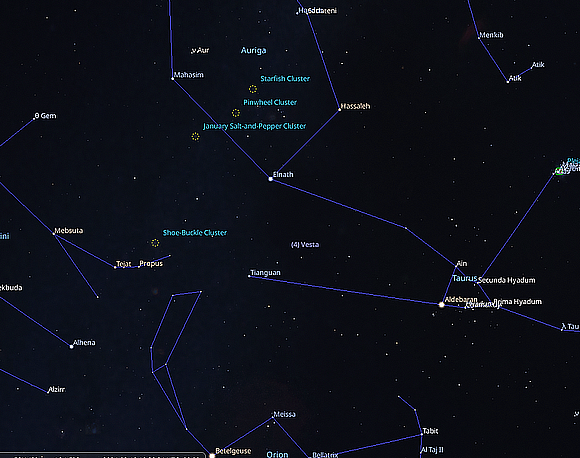

Circumpolar Summer stars are banished to the margins low to the north - as Vega and Deneb in Lyra and Cygnus respectively flirt with the horizon. These circumpolar 'summer triangle' luminaries will endure the winter nights and not seek warmer climes like their brethren member Altair, now long departed. Seemingly stood on its tail, the stars of the familiar Plough asterism identify the location of the Great Bear. The 'pointer stars' in the bowl of the Plough, Dubhe, and Merek point in the direction of Ursa Minor and in particular the Pole star, Polaris. The Celestial dragon – Draco winds its way between the two bears due North, the head of the beast marked by an irregular quadrilateral of stars not far from Vega. Overhead the distinctive ‘W’ pattern of Queen Cassiopeia first occupies the zenith, followed by Perseus (the outline of which resemble a distorted figure Pi symbol) and then the stars of Auriga the charioteer, highlighted by brilliant Capella.

It is the majestic stellar canopy to the South that really attracts the eye. Here the observer is treated to an array of imposing constellations, brilliant stars, and observational interest. At the head of this wondrous stellar cavalcade sit the stars associated with the head of the Bull - Taurus. Known as the Hyades, the distinctive 'V' open star cluster contains the marmalade hue of Aldebaran, 'the eye of the bull’, the most conspicuous presence in the Hyades, but not a true member residing 60 light years away, half the distance of the true Hyades members. Further west of the Hyades, the Pleiades star cluster (Seven Sisters) is a truly beautiful sight in binoculars or low power eyepiece. It is one of the most youthful clusters by stellar standards (150 million years), comprised of many hot, massive B class stars. Keen sighted observers can make out more than seven stars with the naked eye, although most people see six. Binoculars, or very low telescopic magnifications, reveal dozens of stars and the entire cluster contains over 360 members approximately 410 light years away.

By mid-evening, the focal point of the seasonal winter sky, the mighty hunter Orion, stands proud due South, the heart of the glittering tableau ranged around it. Observable from every inhabited place on Earth, the outline of the hunter is quite distinct; the three belt stars set betwixt a larger rectangle, two of these stars in the 'box', in opposing corners are genuine super luminaries’. Rigel illuminates the bottom right of the rectangle, a B7 class blue/white star at least 60,000 times more luminous than our Sun. The top left corner is marked by the fiery hue of Betelgeuse, a red super-giant star of gargantuan proportions, over 400 million miles in diameter and with one foot in the stellar grave. Betelgeuse is considered the strongest candidate of a star to go supernova within the next 10-20 thousand years, the recent temporary fading of this star, maybe an indication of the stars initial behaviour towards its cataclysmic fate. Rigel is also massive enough to end its days as a supernova, tens of millions of years in the future, though short by stellar standards.

Situated just beneath the three stars marking Orion’s belt resides one of the great show piece objects in the night sky, the Orion nebula, the closest region of star formation to us, around 1300 light years. The Nebula, which is thought to be less than 2.4 million years old, consists of a huge cloud of gas and dust perhaps 25 light years in extent. Within the densest clumps of gas, stellar formation is underway, unseen by optical observation.

Seen clearly as a misty smudge through smaller binoculars, telescopically, or with very large binoculars the Orion nebula is quite a breathtaking sight, a swirl of nebulous cloud at the heart of which reside a trapezoid-shaped asterism from which the cluster gets its name, the Trapezium, the four “bully boys” of this stellar crèche. The brightest members are found within 1.5 light years of each other and have estimated solar masses of between 15 and 30 times our Sun. These young OB stars are luminous X-ray sources and are responsible for much of the illumination of the surrounding nebula. The powerful UV radiation force from these stars has hollowed out a cavity in the nebula several light years across, allowing us to see the trapezium stars. It is thought many of the stars forming in the cluster are no more than 300,000 years old, with the brightest as young as 10,000 years. The Trapezium stars are easily seen with modest telescopes, even large binoculars will reveal them.

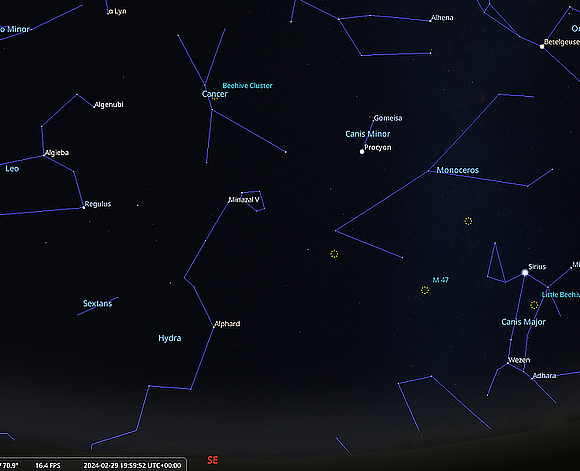

Upper left of Orion stands the Twins of Gemini, marked by the two conspicuous stars, Castor, and Pollux. Castor, the most northerly of the pair, is slightly fainter than twin brother Pollux which shines with a pale amber lustre. Although Castor appears solitary, it is a multiple system of which the brightest two components may be separated in a modest scope, given stable atmospheric conditions. Gemini is home to the fine open cluster M35.

The two hunting dogs of Orion, Canis Major, and Canis Minor, dutifully follow their master across the heavens. The belt stars of Orion point down in the general direction of Canis Major and the most prominent of all night stars, sparkling Sirius, seen low to the SSE. Some distance above and left, solitary Procyon, in the lesser dog of Canis Minor, is yet another highly conspicuous winter jewel, the prominence of both stars primarily due to proximity; 8.6 and 11 light years respectively. Both stars have companion white dwarf stars, though they are very difficult to spot even with quite large instruments.

Look for the faint glow of the winter Milky Way which flows to the left of Orion, separating the two dogs on opposing banks. The dogs' quarry, the timid celestial hare of Lepus, may be traced crouching below Orion and above the southern horizon. Lepus contains one Messier object, M79, a distant globular cluster. Within the faint starry haze left of Orion, a more modern constellation is located, the heavenly unicorn of Monoceros. Its stars are faint and to the naked eye the area looks bland but hidden just beyond our gaze reside a multitude of star clusters and nebulae.

Below the Unicorn, Puppis, part of the now defunct constellation of Argo Navis straddles the S horizon. It too is rich in galactic clusters and nebulae, including the Messier objects M46, M47 and M93. The longest constellation in the heavens (or at least a section of it) occupies much of the sky lower right of Orion. The river Eridanus, the source of which rises just to the right of Rigel, marked by Cursa or beta Eridani, then flows erratically parallel to the southern horizon before plunging through it, journeying far down into the southern hemisphere, ending at a brilliant star called Archenar.

Toward the back end of February, night finds Orion and his entourage already trooping into the west half of the sky, their places taken by an ensemble of spring constellations. The inconspicuous stars of Cancer scuttle after Gemini and mark the border of seasonal change from winter to spring. Leo the lion follows, identified by the distinctive ‘Sickle’ asterism, at the foot of which shines bright Regulus. The faint, but traceable head of Hydra sits below Procyon, and above the Water Snakes chief star, Alphard - the "Lonely one". The clock will be striking midnight before the rest of the snake slithers fully into view. Post midnight, Arcturus in Boötes and Spica in Virgo, join the victims of Hercules, pushing the stars of winter out of the door, ushering in spring, or so we hope.

February 2024 Sky Charts

Additional Image Credits:

- Planets and Comets where not otherwise mentioned: NASA

- Sky Charts: Stellarium Software and Starry Night Pro Plus 8

- Log in to post comments