In this month's Sky Notes:

- Planetary Skylights

- October Meteors & Lunar Eclipse Report

- October Night Sky

- October 2025 Sky Charts

Planetary Skylights: A Brief Guide to October's Night Sky

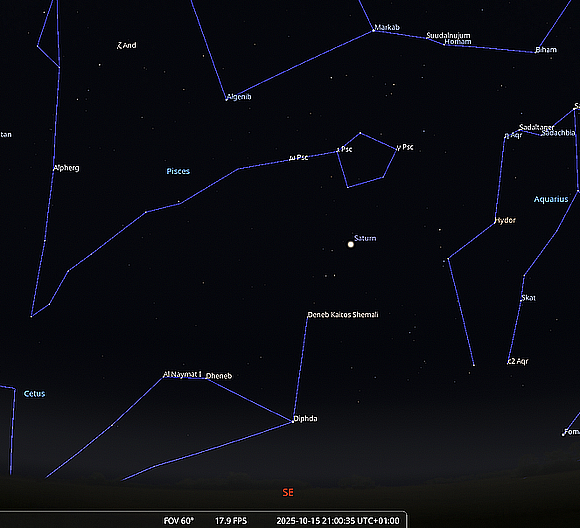

Saturn is already clear of the horizon as darkness falls at the beginning of October, favourably placed in the SE by 21:00hrs. By the time clocks go back in the UK on October 26th Saturn will be crossing the meridian - due south by 21:30hrs, ideally placed for observation. It culminates a respectable 33 degrees above the horizon - still a few degrees shy of the celestial equator which it finally crosses in 2026. Residing amongst the faint star of Aquarius, at magnitude +0.7 Saturn will stand out in a region of the sky devoid of brighter stars.

Saturn is already clear of the horizon as darkness falls at the beginning of October, favourably placed in the SE by 21:00hrs. By the time clocks go back in the UK on October 26th Saturn will be crossing the meridian - due south by 21:30hrs, ideally placed for observation. It culminates a respectable 33 degrees above the horizon - still a few degrees shy of the celestial equator which it finally crosses in 2026. Residing amongst the faint star of Aquarius, at magnitude +0.7 Saturn will stand out in a region of the sky devoid of brighter stars.

Through the eyepiece Saturn is often a glorious sight but this being a ring plane crossing year currently the tilt of the rings is only around 2 degrees in orientation. By November the rings will be edge on once more. You can spot Saturn's largest moon, Titan, in most apertures, visible as a speck of light nearby. Several more of Saturn’s moons are also visible to 'amateur telescopes' especially when the rings are closed. Rhea, Tethys, Dione should all be glimpsed in instruments above 150mm (6"). On October 5th a Moon resides just below Saturn.

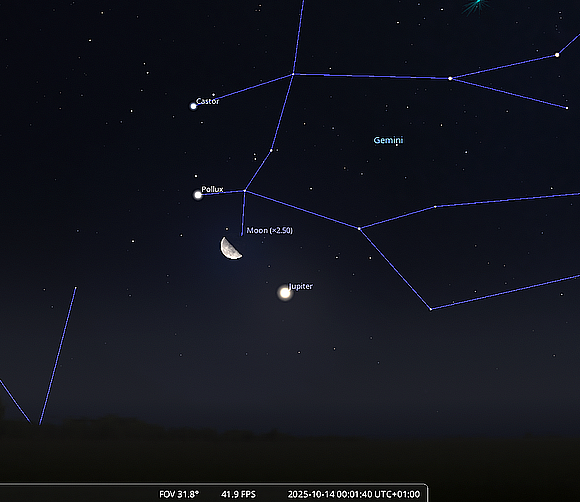

Jupiter’s presence in the night sky grows ever more conspicuous, visible shortly before midnight at the start of October and by 21:00hrs GMT at the end. Residing just below Gemini, Jupiter’s movement in prograde motion (eastwards) in relation to the background stars has slowed almost to a halt. By the end of October, it will start to move in retrograde motion – westwards. At magnitude -2.25 Jupiter is already conspicuous to the eye becoming even more so as it heads toward opposition in a few months’ time.

Jupiter’s presence in the night sky grows ever more conspicuous, visible shortly before midnight at the start of October and by 21:00hrs GMT at the end. Residing just below Gemini, Jupiter’s movement in prograde motion (eastwards) in relation to the background stars has slowed almost to a halt. By the end of October, it will start to move in retrograde motion – westwards. At magnitude -2.25 Jupiter is already conspicuous to the eye becoming even more so as it heads toward opposition in a few months’ time.

Jupiter remains an impressive object even when observed through small telescopes, with its oblate disk measuring almost 40 arc-seconds clearly visible in the eyepiece. Observers can identify the planet's darker atmospheric bands, the Great Red Spot (when present), and nearby Galilean moons. These moons complete their orbits within days to weeks, while Jupiter itself rotates in under ten hours. The view to the amateur observer is therefore of great interest as the configuration changes constantly.

Larger instruments offer more enhanced views of Jupiter’s cloud features, the observer positively identifying the Great Red Spot more easily as well as noting any moon shadow transits. These will be highlighted in the coming months as Jupiter becomes an easy evening target.

Neptune is well placed for telescopic observation having reached opposition last month. The outermost planet can be tracked down approximately two-degrees upper left of Saturn. With a magnitude of +7.8, Neptune is observable with binoculars, although a telescope is necessary to discern its small blue-grey disk, which measures 2.8 arc-seconds in diameter. Instruments of 100mm (4") aperture are generally adequate for this but telescopes exceeding 150mm (6") will reveal it more clearly.

Neptune is well placed for telescopic observation having reached opposition last month. The outermost planet can be tracked down approximately two-degrees upper left of Saturn. With a magnitude of +7.8, Neptune is observable with binoculars, although a telescope is necessary to discern its small blue-grey disk, which measures 2.8 arc-seconds in diameter. Instruments of 100mm (4") aperture are generally adequate for this but telescopes exceeding 150mm (6") will reveal it more clearly.

Uranus lies in Taurus, approximately five degrees below the Pleiades star cluster. It is located roughly midway between the star pairings of A1 & A2 Tau and 13 & 14 Tau. With a magnitude of +5.8, Uranus is technically visible to the naked eye under very dark skies but will be a tricky spot from UK shores. Through binoculars, Uranus appears as a faint point, telescopes with apertures of at least 80mm (3+ inches) are necessary to resolve its small 3.7 arcsecond greenish disk, which becomes more distinct in instruments of 150mm (6”) or larger.

Uranus lies in Taurus, approximately five degrees below the Pleiades star cluster. It is located roughly midway between the star pairings of A1 & A2 Tau and 13 & 14 Tau. With a magnitude of +5.8, Uranus is technically visible to the naked eye under very dark skies but will be a tricky spot from UK shores. Through binoculars, Uranus appears as a faint point, telescopes with apertures of at least 80mm (3+ inches) are necessary to resolve its small 3.7 arcsecond greenish disk, which becomes more distinct in instruments of 150mm (6”) or larger.

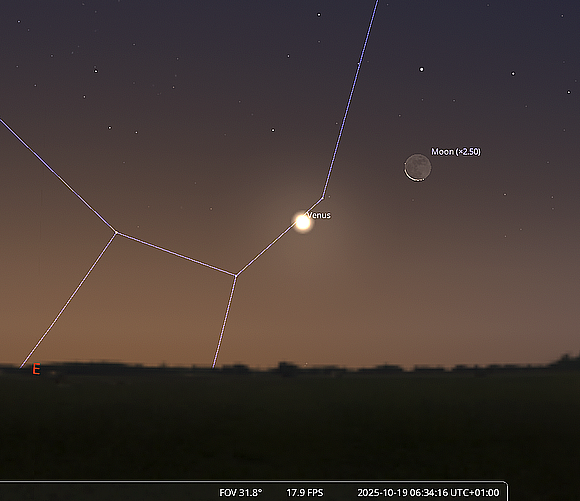

Venus, commonly referred to as the 'morning star', is visible low in the eastern dawn sky, observable from 05:15hrs at the start of the month. At magnitude -4.0, Venus will be highly conspicuous but if the observers view to the east is badly compromised, they may miss it. Venus gradually slides towards the ESE over the course of the month. After the clocks go back on Oct 26th, Venus will be visible from 05:30hrs until 06:30hrs but it has not been the most favourable apparition for observers at mid-northern latitudes.

Venus, commonly referred to as the 'morning star', is visible low in the eastern dawn sky, observable from 05:15hrs at the start of the month. At magnitude -4.0, Venus will be highly conspicuous but if the observers view to the east is badly compromised, they may miss it. Venus gradually slides towards the ESE over the course of the month. After the clocks go back on Oct 26th, Venus will be visible from 05:30hrs until 06:30hrs but it has not been the most favourable apparition for observers at mid-northern latitudes.

October Meteors

Meteor activity throughout October is relatively high, three meteor showers having peaks during the month. The Orionids (Oct 16- 27) are usually October's most prolific meteor shower, peaking over the night of Oct 21/22. Orionids are associated with Comet Halley (along with May's Eta Aquarids) but the Orionids are more favourable for northern hemisphere observers, with the radiant situated high in the south by early morning hours. Prospects for the shower are good this year with the Moon out of the way completely.

Orionids are swift moving, often producing persistent trains. The radiant rises around 22:00hrs BST but as usual early morning will offer the greatest chance of spotting a meteor, say 02:00hrs when the radiant lies 30 degrees above the east horizon.

The Southern Taurids peak on October 10th, rates being little more than sporadic levels (5 per hour). Moonlight from a waning gibbous Moon will hamper sightings this year.

The weak Piscid shower has three peak dates, Oct 13th normally the optimum one. Observed rates are little better than sporadic levels - around 3-7 per hour. Piscid meteors are often slow, of long duration, but not very brilliant. Moonlight will interfere to some extent in the early morning hours.

Perhaps the most interesting shower is the Giacobinids or Draconids (Oct 6 -10th, peaking on the 8/9th), which are associated with the periodic comet Giacabini-Zinner (6yrs). The shower is very erratic but can produce outbursts of activity. Unfortunately, moonlight will hamper this year. The Draconids radiant lies within the constellation of Draco, which is located high up in the NW winding its way between the two celestial bears of Ursa Major and Minor. Rates vary but are normally low, around the 7-12 per hour mark. Moonlight will be an issue this year.

Lunar Eclipse Report

The total lunar eclipse on September 7th, visible only near the end of totality as the Moon rose for UK observers, was only partly seen by many in the district. I suppose we should be grateful that cloud cover above the east-southeast horizon only partly obscured the event, admittedly the ‘total’ part around 19:45hrs.

It wasn't until 20:25hrs or thereabouts the Moon finally shrugged off its cloud blanket, Earth's umbral shadow already retreating halfway across the lunar surface. The rest of the 'noticeable' partial stage was occasionally viewed through a thin veil of cloud, but still apparent to the public, some of whom probably thought the Moon was at Quarter phase.

The next respectable lunar eclipse for UK observers, a partial, occurs in the early morning hours of Aug 28th next year (2026). The next total lunar eclipse visible from the UK is Dec 31st, 2028 - around teatime - seeing out the old year in style!

October Night Sky

Recent years have seen October just as conducive for observing as September, perhaps more so, presenting an excellent opportunity to be outside observing when skies are clear.

October certainly feels a different beast to those I recall when I first started to learn to find my way around the night sky aged seven or eight.

Armed with just a set of 2.5x magnification 'pop-up opera glasses', popular in the early 1970s, a few basic astronomical books and a passion to learn, the October night sky felt like a treasure map whose secrets were to be discovered.

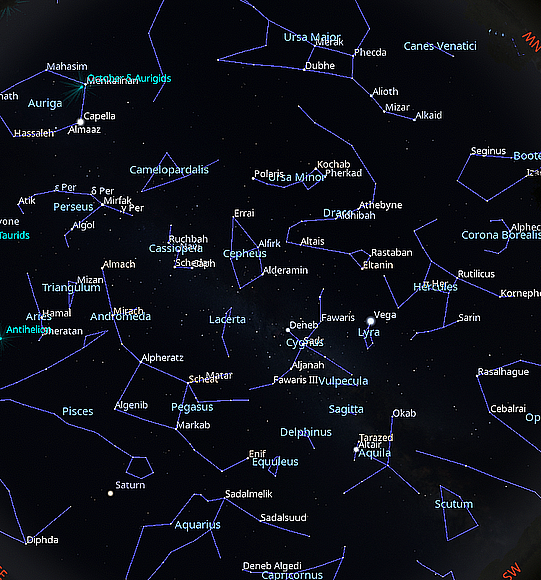

As darkness falls at the start of October, summer constellations are ideally placed, those associated with autumn take centre stage mid-evening and by the month's end the vanguard of winters brilliant stellar canopy starts to climb into the sky.

I took my first celestial steps tracking down one of best-known star patterns, the Plough, the outline of which resembles a ‘dot to dot’ saucepan (also known as the Big Dipper). The Plough is really an asterism, a distinctive pattern within a constellation, in this case Ursa Major, the Great Bear. Five of the stars forming the Plough asterism are genuinely associated, sharing the same 'proper motion' through space. These, along with several other stars in the northern part of the sky, are members of the Ursa Major moving star cluster.

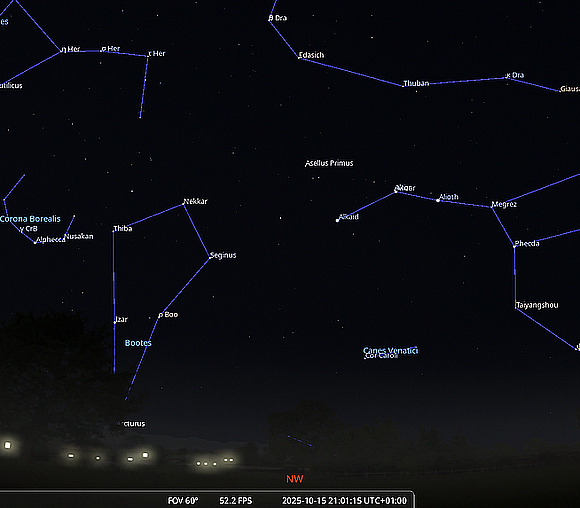

Throughout autumn evenings the Plough reaches its lowest station on its endless journey around the celestial pole, located a couple of hand-spans above. Note the middle star in the handle of the Plough. If you have decent eyesight, you should be able to detect this star is double. Binoculars show Mizar and Alcor well, but a telescope also reveals that Mizar itself is a striking double star. Numerous deep sky objects are dotted around Ursa Major, most of which require a 150mm (6") telescope to appreciate, but the twin galaxies of M81 and M82 are somewhat brighter, visible even in binoculars as smudges of light.

Ursa Minor is less conspicuous, but the constellation is home to Polaris, the present pole star, situated at the tip of Ursa Minor. Use the ‘pointer’ stars - the rear two stars in the bowl of the Plough to locate it.

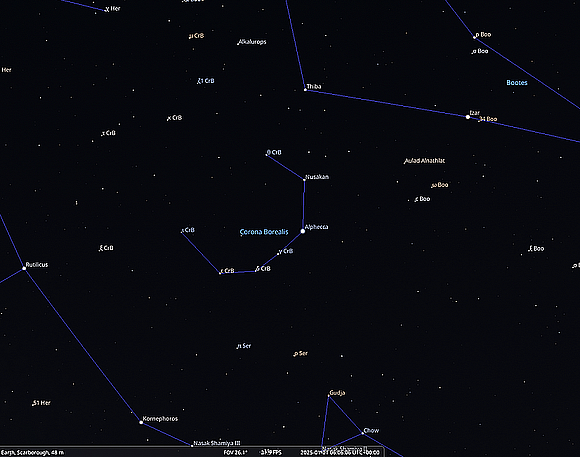

Follow round the curve of the Plough's handle to locate Arcturus, the brilliant star low in the WNW at the foot of the outline of Boötes the Herdsman. To the upper left of Arcturus look for the delicate starry circlet of Corona Borealis - the Northern Crown. Its leading star, Gemma, (also called Alphecca) is set amid this pleasing arrangement. Astronomers the world over are eagerly waiting for T Coronae Borealis (T CrB), a recurrent nova star, to flare up after 80 years. UK observers will be particularly nervous as Corona drops closer to the NW horizon with the 'Blaze Star' overdue and predictions hinting at a November outburst.

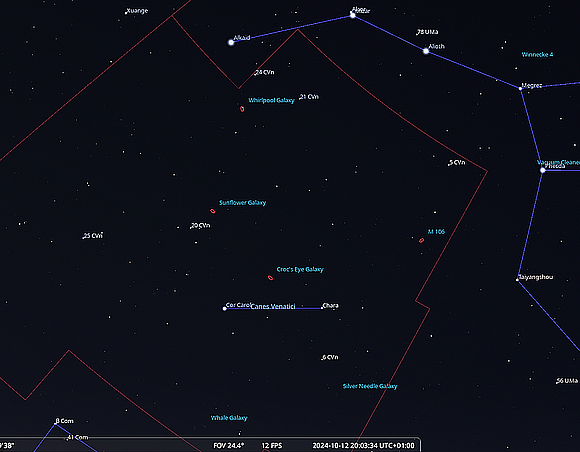

Located some distance beneath the handle of the Plough lies Canes Venatici; the Herdsman’s dogs marked by just two stars. The brighter one, Cor Caroli, meaning Charles’s heart, was named in honour of King Charles II. The constellation may be small but contains many deep sky objects within its confines including M51 - the Whirlpool galaxy, M3 a fine globular cluster, M63, M94, M106 - all galaxies, as well as NGC 4631 - the Whale galaxy.

Winding between the two celestial bears are the stars of the celestial dragon - Draco, the head of which resides not far from Vega. Overhead the faint pattern of Cepheus resembles the outline of a crooked house. It contains no apparent ‘showpiece’ objects but does contain the variable stars Delta and Mu. Mu is known as the Garnet star, one of the reddest stars visible in the heavens. Delta Cephei is the prototype star of its class, very large, luminous, yellow stars the periods of which are directly linked to their mass. Such stars are seen as ‘standard candles’ being of immense value in estimating both stellar and galactic distances.

Residing adjacent to Cepheus sits the distinctive pattern of Queen Cassiopeia the outline of which resembles that of the letter ‘W’ or ‘M’. It is a constellation well worth exploring with binoculars or telescope, especially as the Milky Way flows through it. Following Cassiopeia, climbing up toward the zenith from the NE is ‘son in law’ Perseus, the pattern of which reminds a little of Isobar lines sweeping across a weather chart.

Beta Persei or Algol, is a most interesting variable star, an eclipsing binary system causing Algol to 'wink' every 3rd day. It is known as the 'Demon' star, more on this next month. Perseus also contains some fine deep sky objects, particularly the Perseus double cluster regarded by many amateur astronomers as one of the loveliest sights visible in smaller instruments, a stellar jewel box!

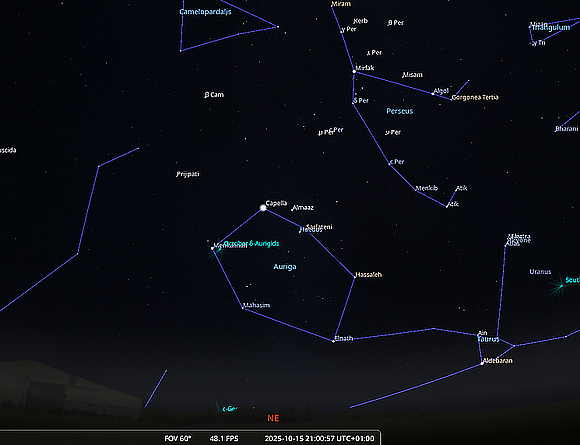

Following Perseus, climbing away from the NE horizon is the brilliant star Capella, chief luminary in the pentangle outline of Auriga the charioteer. Capella is a circumpolar winter star spending its summer low to north before climbing up overhead as winter commences.

Anyone not familiar with the workings of the night sky may naturally assume that although autumn has arrived, stars associated with summer have departed. Yet as twilight deepens many constellations associated with summer remain well placed for viewing.

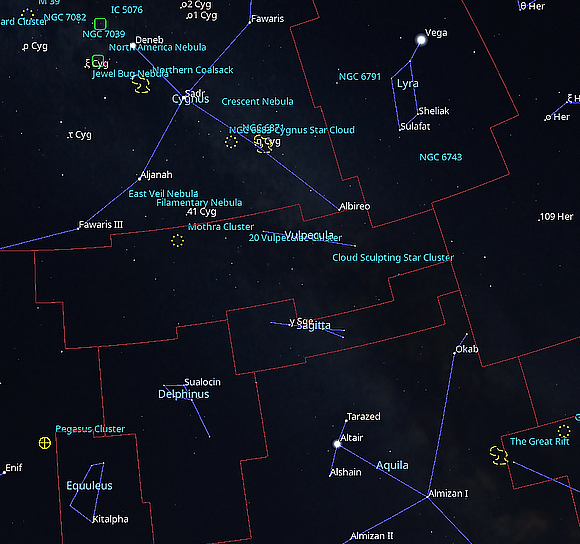

Particularly noticeable are the three bright stars of the summer triangle., the lovely steely blue hue of Vega in the lozenge shaped group of Lyra is most conspicuous high in the NW.

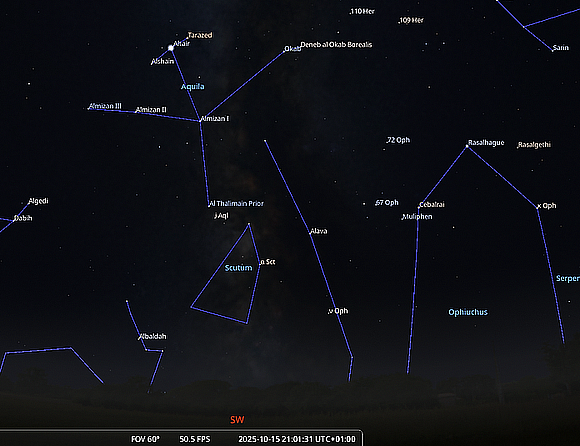

Cygnus the Swan, also known as the Northern Cross, hangs like a crucifix from its chief star Deneb high to the west. Both groups are circumpolar, visible all year, being sufficiently far north of the celestial equator not to set from our latitude. Of the summer trio only Altair, chief star in Aquila the Eagle migrates south for the winter, setting due west later in the month shortly after 22:30hrs.

A short distance above Altair in Aquila, note the small arrow shaped group of Sagitta together with the close-knit group of Delphinus situated to its left. Delphinus is one pattern that with a little imagination does resemble the outline of a dolphin leaping out of water. It is sometimes known as ‘Jobs coffin'. Between Cygnus and Sagitta, a smattering of stars mark Vulpecula - the Fox in which the fine planetary nebula M27 - the Dumbbell resides.

Stradling the horizon to the south lie the stars of Sagittarius - the Archer, never seen in its entirety from UK shores. If skies are transparent look for the large asterism referred to as the ‘Teapot’, the outline of which resembles a more ‘angular’ type of pot slightly tilted as if pouring a cuppa! Sagittarius is chock full of DSOs and worth exploring if skies are particularly transparent. See ‘In Focus article - The Archer - part 2’.

The eastern aspect of the sky is dominated by just a few constellations, particularly the winged horse Pegasus, which stands 2-3 hand-spans above the horizon. It is best identified by autumn's signature asterism the “the great square”, an arrangement of four stars enclosing a large area of sky seemingly devoid of naked eye stars. The asterism is particularly useful as a signpost to those fainter constellations visible low to east and southeast.

Travelling clockwise from the top left-hand star in the square, Alpheratz, we in turn encounter Scheat, Markab and Algenib. Alpheratz (alpha andromeda), the main body of which extends away to the east and is the jump off point for locating the Andromeda galaxy, our sister galaxy (see last month - September Night Sky).

Below Andromeda sit two small constellations, Triangulum, below which lie the crooked line of stars marking Aries - the Ram. Triangulum contains the third spiral galaxy in the 'local group' in which the Milky Way and Andromeda galaxies are members. M33 (the other pinwheel galaxy in the sky) is only a third the size of these galaxies, appearing face on to us and seen as a misty patch in binoculars or rich field telescopes.

Return to the square and by projecting a line diagonally from Alpheratz down through Markab (alpha Pegasi), the bottom right star of the square, will guide the observer to a zig-zag asterism of stars representing the ‘water jar’, part of the constellation of Aquarius, the Water Bearer. According to one legend this group represents Zeus pouring down the waters of life from heaven. Several stars in Aquarius have names beginning with ‘Sad’ which in Arabic means ‘luck’ (Sa’d). Continue this direction of travel and you run into Capricornus located above the SSW horizon.

Toward the end of October, the most southerly first magnitude star to rise over the UK begins its short apparition. Fomalhaut marks the mouth of Pisces Austrinus, the Southern Fish, into which the waters of Aquarius pour. Conveniently, a line drawn down through the two right hand stars in the ‘square’ (Scheat and Markab) point directly to its location just above the S horizon. Fomalhaut is located 25 light years away and has at least one planet orbiting around it.

Should conditions allow then, please do take the opportunity to investigate the autumn night sky, it really is a vista of all seasons!

October Sky Charts.

Additional Image Credits:

- Planets and Comets where not otherwise mentioned: NASA

- Sky Charts: Stellarium Software and Starry Night Pro Plus 8

- Log in to post comments