It was a day full of excitement and trepidation, as the drama of the Philae Lander's despatch from the Rosetta's satellite took place, and Philae drifted in super-weak gravity towards the surface on a 7-hour journey to Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko.

It was a day which almost didn't happen, as overnight preparations revealed a malfunction in the thruster which was to press Philae to the ground immediately on landing while harpoons tethered it to the comet surface were fired. But the decision was taken to go ahead, and at about 08:30h GMT Philae successfully separated from Rosetta and began its descent.

The landing was confirmed at around 16:05h GMT and verified a few minutes later. But all was not as it seemed...

It was a day full of excitement and trepidation, as the drama of the Philae Lander's despatch from the Rosetta's satellite took place, and Philae drifted in super-weak gravity towards the surface on a 7-hour journey to Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko.

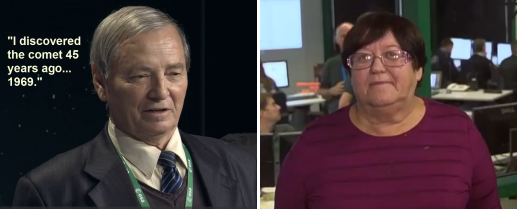

Ukranian Astronomer Klim Churyumov and Tajikistani Astronomer Svetlana Gerasimenko were

on-hand as Philae landed on their comet.

It was a day which almost didn't happen, as overnight preparations revealed a malfunction in the thruster which was to press Philae to the ground immediately on landing while harpoons tethered it to the comet surface were fired. But the decision was taken to go ahead, and at about 08:30h GMT Philae successfully separated from Rosetta and began its descent.

The landing was confirmed at around 16:05h GMT and verified a few minutes later. But within a couple of hours it was becoming clear that something was amiss. Philae had landed in bullseye position, right in the middle of its target zone. But Philae's signal was periodically dropping and some of the instrument readings being returned suggested the lander was rotating. The transmission window, as Rosetta disappeared behind the back of the comet, ended half-an-hour earlier than expected, and we were left with an overnight cliff-hanger.

In the morning anxious scientists, assembled journalists and an expectant world received news: not only had Philae's thruster failed, but its harpoons had not successfully fired and the lander had bounced perhaps hundreds of kilometers into the air, spinning gently for a couple of hours before bouncing a second time before landing somewhat precariously against a cliff wall, with at least one foot in the air.

Philae's final landing place was in the shadows: instead of a hoped-for 6 hours sunlight per day on three panels, one panel received just 1h 20m of sunlight, and the other two just twenty minutes. Philae's secondary batteries will only start charging when sun sun warms them from the shade temperature of -50 to -90℃, up to 0℃; and that just isn't going to happen in the near future - at least until the comet gets much closer to the sun.

So the race was on in earnest, to accomplish maximum science within the 65 hour operational period of the primary batteries. Ten experiments, each supported by a research team, were waiting to receive data, and collection started automatically within 10 minutes of the initial landing.

Data flowed in. Work on analysis began. And through it all the stakeholders asked some major questions about what to do with the limited time available... should they use Philae's mechanical instruments to try and engineer another bounce, in hope of reaching a better spot? At best, such an intervention might give the opportunity for many more experiments; but at the big risk of making the situation worse. Could they risk using the drill to try and collect samples from the comet surface, or would it tip over the lander from its present - perhaps precarious - position? And would the primary battery last long enough to receive the data from Philae's second day of experiments?

Saturday's news was greeted with relief: the batteries had held and the experimental data were returned. The drills were activated, and time will tell whether any material they pulled into the on-board ovens have produced useful results. And the Philae controllers successfully rotated the solar panels into the most favourable position to receive available light in its shady hollow.

Now Philae is asleep. It may perhaps awake, months from now, if conditions closer to the sun are more favourable. There has been a drip-feed of minor Rosetta discoveries since the excitement, but we will have to wait until next month for the next major scheduled update from the Rosetta team.

One outstanding point of public interest is where exactly Philae finally parked itself. Mission scientists hope to derive quite an accurate position from close data analysis, but that hasn't arrived yet. "Watch this space", as they say.

---

Matthias Malmber is a Swedish 3D expert and space hobbiest who has used his skills to estimate Philae's final landing place. Although he gives strong caveats that he's not a scientist and his results could be completely wrong, he's made this fascinating animated prediction based on public information.

- Log in to post comments