In this month's Sky Notes:

Planetary Skylights - Brief

Jupiter dominates the night sky. Saturn fades into twilight by the month's end, Neptune is lost earlier. Uranus is observable with a telescope below the Pleiades. Mercury undergoes a fine evening apparition for UK observers and is joined by Venus at the end of the month.

After reaching opposition in January, Jupiter continues to dominate in the February night sky at magnitude of -2.66, culminating around 58-degrees in elevation. Located in Gemini - the Twins, Jupiter's retrograde motion will slow to a halt during February before resuming normal prograde travel. The Moon pays Jupiter a visit near the end of the month on the 26th and 27th.

After reaching opposition in January, Jupiter continues to dominate in the February night sky at magnitude of -2.66, culminating around 58-degrees in elevation. Located in Gemini - the Twins, Jupiter's retrograde motion will slow to a halt during February before resuming normal prograde travel. The Moon pays Jupiter a visit near the end of the month on the 26th and 27th.

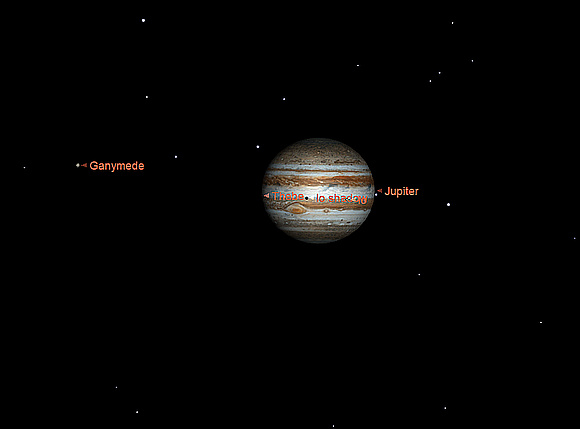

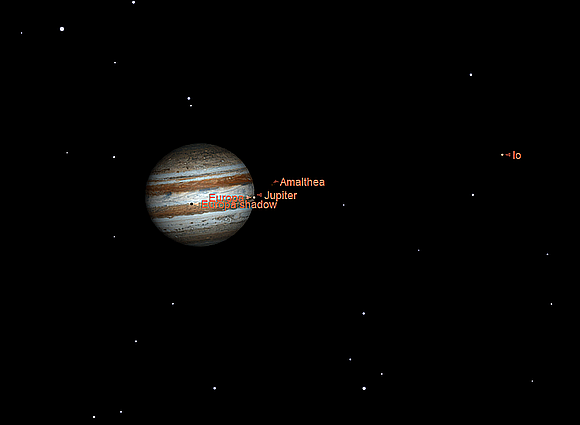

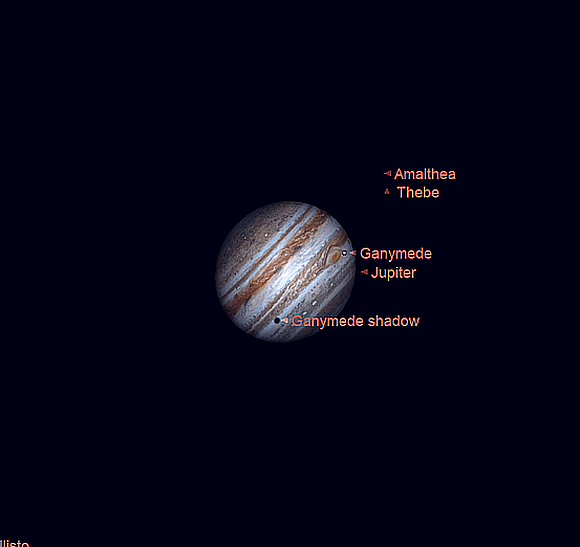

Due to its large angular size in the eyepiece - a whopping 45 arcseconds in diameter, Jupiter is an obvious target, whatever sized instrument employed. The noticeable oblate disk, crossed by darker belts and zones is readily visible in instruments of 60mm (2.5”) aperture. Larger apertures show increasingly finer details including the northern and southern temperate belts. The appearance of the Galilean moons is also a striking feature of the Jovian system, visible as specks of light - even in binoculars.

When turned in our direction, look for the great red spot (GRS) - a colossal storm feature, visible on the south equatorial belt. Ever present, in recent decades the GRS has diminished in size and hue intensity by perhaps a third. It may be observed in 100mm (4”) scopes but will be more obvious with 150mm (6”) instruments at medium powers. The GRS is favourably orientated towards Earth during the evening (19:00-21:00hrs) on the following dates. February 1st, 6th, 8th, 13th, 18th, 20th & 25th. Bear in mind, Jupiter's rotational period is surprisingly short -just under 10 hours and given that its current nightly observing window exceeds 10 hours, one full rotation may be observed, so that the GRS will be visible at some point during the hours of darkness throughout February.

Observe Jupiter regularly and you will note the 'dance' of the Galilean moons; Io, Europa, Ganymede and Callisto around Jupiter, resulting in a different configuration each night. Look for moon shadow transits (visible as black dots transiting the disk of Jupiter) which are particularly fascinating to follow. With good ‘seeing’ conditions, apertures exceeding 100mm (4") using medium/high magnification should suffice. The moons themselves are more difficult to spot as they pass in front of Jupiter, requiring larger apertures.

The most favourable evening shadow transits in February are Ganymede - Feb 4th @ 18:30hrs GMT. Callisto - Feb 12th @ 21:10hrs. Europa - Feb 19th @ 21:15hrs. Io - Feb 22nd @ 21:30hrs,

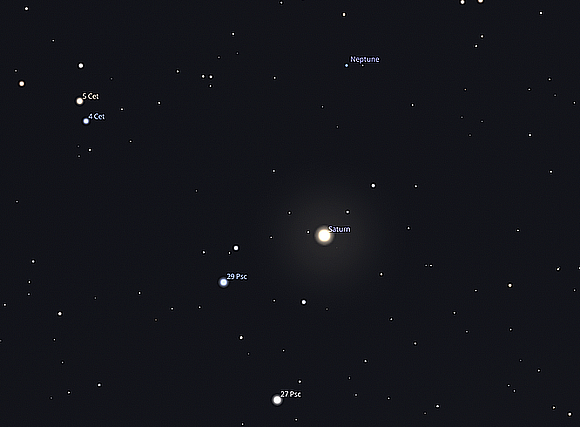

Saturn continues to drop closer to the western horizon as it nears the end of its current apparition, setting shortly after 19:00hrs from UK shores by the end of the month. Observations of Saturn will be more viable earlier in the month, before it drops too low. At magnitude +0.88, Saturn appears conspicuous against the faint stellar backdrop it resides against, the border region of Pisces, having recently moved out of Aquarius. When Saturn eventually returns to the morning sky late in the spring, it will have also crossed the celestial equator, slowly gaining in declination in the coming years.

Saturn continues to drop closer to the western horizon as it nears the end of its current apparition, setting shortly after 19:00hrs from UK shores by the end of the month. Observations of Saturn will be more viable earlier in the month, before it drops too low. At magnitude +0.88, Saturn appears conspicuous against the faint stellar backdrop it resides against, the border region of Pisces, having recently moved out of Aquarius. When Saturn eventually returns to the morning sky late in the spring, it will have also crossed the celestial equator, slowly gaining in declination in the coming years.

Observations of Saturn this side of summer continue to reveal the rings still very closed after last year's ring plane crossing events. This does however allow observers the opportunity to spy several of Saturn’s satellite moons normally hidden in ring glare. Dione, Rhea, and Tethys should all be visible with modest-sized telescopes. Titan—by far Saturn’s largest moon—is typically seen as a nearby point of light. View on February 19th when a crescent Moon lies to the right of Saturn.

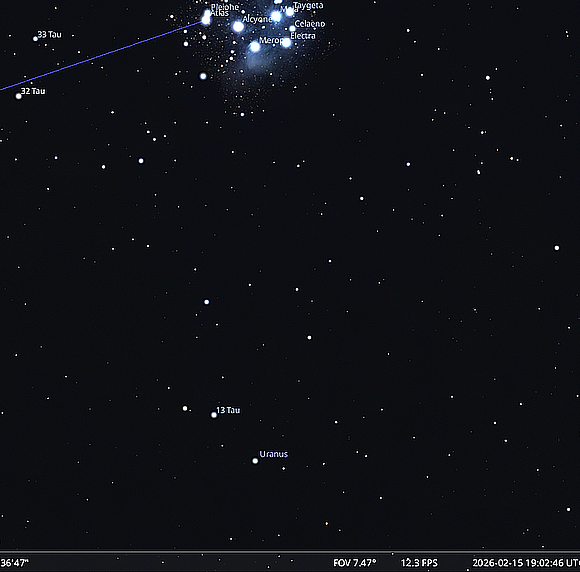

Uranus is well placed to track down in the evening sky approximately 4 degrees lower right of the Pleiades star cluster in Taurus. At mag +5.6 Uranus is technically visible to the naked eye but requires binoculars just to show as a speck. Instruments of 80mm plus (3"+) will hint at a planet and above 150mm (6") should clearly define the very small 3.7 arcsecond grey-green disk.

Uranus is well placed to track down in the evening sky approximately 4 degrees lower right of the Pleiades star cluster in Taurus. At mag +5.6 Uranus is technically visible to the naked eye but requires binoculars just to show as a speck. Instruments of 80mm plus (3"+) will hint at a planet and above 150mm (6") should clearly define the very small 3.7 arcsecond grey-green disk.

Uranus is located below, and right of the pairing of 13 and 14 Tau (both 5th magnitude stars), and having spent January edging away from them in retrograde motion is now slowly edging back. Uranus culminates over 50 degrees above the south horizon, not setting until the early morning hours.

Neptune remains visible above the horizon throughout most of February; however, it will become increasingly difficult to observe from mid-month onwards as twilight and low altitude affect its visibility. The faint planet sets around 19:30 GMT in the UK. The nearest designated star to Neptune is 29 Psc, a 5th magnitude star only just visible to the naked eye. The planet Saturn will be a more useful aid, as it moves from 1.5 degrees below Neptune in the first week of February, to less than one degree west of Neptune near the end of the month.

Neptune remains visible above the horizon throughout most of February; however, it will become increasingly difficult to observe from mid-month onwards as twilight and low altitude affect its visibility. The faint planet sets around 19:30 GMT in the UK. The nearest designated star to Neptune is 29 Psc, a 5th magnitude star only just visible to the naked eye. The planet Saturn will be a more useful aid, as it moves from 1.5 degrees below Neptune in the first week of February, to less than one degree west of Neptune near the end of the month.

Neptune itself shines at an 8th magnitude, appearing as a tiny disk 2.4 arc-second across through the eyepiece of a telescope, binoculars will reveal it as a 'star like' object only. Observers will require a minimum aperture of 100mm (4") at 100x magnification, and good viewing conditions to discern this, although larger apertures would be more advantageous for better definition.

Mercury commences its most favourable evening apparition this year for UK observers shortly before mid-month. Start looking for the elusive innermost planet just above the west-southwest horizon from February 12th around 17:45 hrs - about 40 minutes after sunset. At magnitude -1.02, Mercury is brightest at the start of the apparition, however, twilight and its very low altitude will reduce its visibility.

Mercury commences its most favourable evening apparition this year for UK observers shortly before mid-month. Start looking for the elusive innermost planet just above the west-southwest horizon from February 12th around 17:45 hrs - about 40 minutes after sunset. At magnitude -1.02, Mercury is brightest at the start of the apparition, however, twilight and its very low altitude will reduce its visibility.

For the next week Mercury gains elevation and should be readily discernible with binoculars. On February 18th Mercury is in conjunction with a crescent Moon and a day later reaches greatest eastern elongation. It will then be over 9 degrees above the horizon by 18:10 hrs. Mercury then slides back to the west horizon diminishing in brightness as it does so. A very slim crescent Moon may be glimpsed below Mercury on the 18th.

Venus returns to the evening twilight sky this month. Look for it just above the west horizon from 17:45 hrs from the 18th onwards. Although very bright, this will be tempered by the twilight and low altitude. On the 27th Venus lies lower left of Mercury at 18:00hrs. As we head through March, Venus will rapidly gain altitude in the evening twilight sky.

Venus returns to the evening twilight sky this month. Look for it just above the west horizon from 17:45 hrs from the 18th onwards. Although very bright, this will be tempered by the twilight and low altitude. On the 27th Venus lies lower left of Mercury at 18:00hrs. As we head through March, Venus will rapidly gain altitude in the evening twilight sky.

February Meteors

February has no notable meteor showers. The Alpha Aurigids, peaking mid-January to mid-February, are minor with only 2-5 meteors per hour, equivalent to sporadic meteor rates. Despite this, the period from late January to March has been dubbed the 'fireball season', any meteors visible often bright. It may be remnants of an old, depleted shower, the meteoroids denser in nature like the Geminids. If you see a meteor heading away from Auriga, note it; otherwise, it's likely just sporadic.

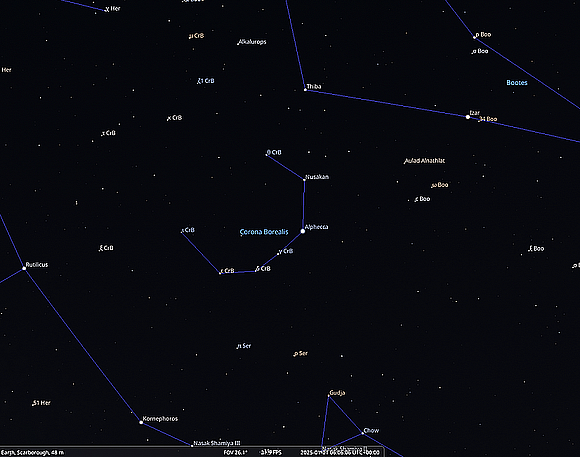

T Corona Borealis.

The wait goes on for T Coronae Borealis (T CrB), 'the Blaze Star,' to go Nova. Located in the constellation Corona Borealis, this 10th magnitude binary star and recurrent nova brightening to 2nd magnitude roughly every 80 years.

Corona does not become visible until the midnight hour, although by the end of February it will be on show low to NE by 21:30hrs. Keep tabs across the media.

Aurora Report

Jan 20th - 19:55hrs - Saltwick - 3 Sisters. OM-1 12mm lens f2.8 ISO 3200 - 8 secs.

(Click for full image)

January saw several Aurora displays visible from the UK, though not necessarily from our neighbourhood. Given the weather in January, it was a wonder anything was observed, but there were a few clear nights. The major aurora seen from parts of the UK on Jan 19th was not one of those clear sky nights on the North Yorkshire coast. Strong activity continued the following day, fortunately coinciding on the evening of the 20th with a partly clear evening.

Noting that charts were in the 'red', Mark jumped in the car and made his way to Saltwick to see what was visible. Conditions were far from ideal for imaging - a cold, strong gusty, wind and waterlogged underfoot conditions, but after a few dodgy moments on the path down to the beach and on the cliff, some images were captured.

Auroral intensity had been greatest early evening (according to the chart), and by 19:50hrs was on the wane, although structure was still noticeable - hue mostly green, with some magenta bands. With wind gusts intensifying and cloud spilling in, Mark finally gave into the thought of a hot chocolate, hands froze, trousers dirty, boots clogged with mud. The things we do!!

February Night Sky

As winter’s darkest days start to recede, evening twilight is noticeably lengthening with meteorological spring arriving on March 1st. Traditionally, February is known for unleashing the harshest winter weather, sometimes bringing the infamous ‘beast from the east’ or bursts of Arctic cold. However, increasingly the month can also be mild, hinting at spring—especially as it draws to a close. Irrespective of the temperature, as long as skies are clear to some extent, February’s night skies are especially stunning, inviting stargazers of all abilities to explore deeper.

As February commences the western aspect of the early evening sky is still dominated by autumnal constellations, particularly the great square of Pegasus. Sprouting from the winged horse, the stars of Andromeda reach toward the figures of Perseus and distinctive Cassiopeia high in the NW. Circumpolar Summer stars are banished to the margins low to the north, Vega and Deneb in Lyra and Cygnus respectively flirting with the horizon. These circumpolar 'summer triangle' luminaries will endure the winter nights, not seeking warmer climes like their brethren member Altair, now long departed.

Seemingly stood on its tail above the NE horizon, the stars of the familiar Plough asterism identify the hind quarters of the Great Bear. Utilise the 'pointer stars' in the bowl of the Plough, Dubhe and Merek to track down the Pole star, Polaris in the constellation of Ursa Minor located to the left of the Plough.

The Celestial dragon – Draco, winds between the two bears, the head of the beast marked by an irregular quadrilateral of stars upper right of Vega almost due north. Overhead the distinctive ‘W’ pattern of Queen Cassiopeia first occupies the zenith, followed by Perseus (the outline of which resemble a distorted figure Pi symbol), before the pentangle shape of Auriga the charioteer, highlighted by brilliant Capella, does likewise.

Ranged across the sky to the south, the majestic stellar canopy of winter never fails to impress. Here the observer is treated to an array of imposing constellations, brilliant stars, and observational interest. Leading the way, the distinctive pattern of the Hyades - the head of Taurus, a 'V' arrangement pointing to the west. The open cluster contains the fiery hue of Aldebaran, 'the eye of the bull’, however the lead star in Taurus is not a genuine member residing 60 light years away, half the distance of true Hyades members.

West of the Hyades, the Pleiades star cluster (Seven Sisters) is a beautiful sight in binoculars or low power eyepiece. It is one of the most youthful clusters by stellar standards (150 million years), comprised of many hot, massive B class stars. Keen sighted observers can make out more than seven stars with the naked eye, although most people see six. Binoculars, or very low telescopic magnifications, reveal dozens of stars and the entire cluster contains over 360 members approximately 410 light years away.

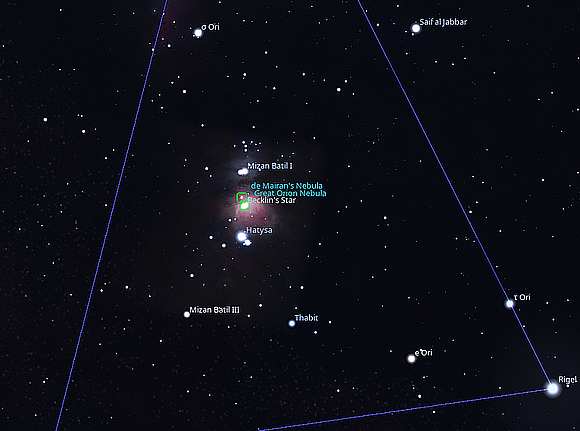

By mid-evening the mighty hunter, Orion, stands proud due South, the focal point of winter seasonal constellations. Observable from every inhabited place on Earth, the outline of the hunter is quite distinct; the three belt stars set betwixt a larger rectangle. Two of these stars in opposing corners of this oblong are genuine super luminaries’. Rigel illuminates the bottom right of the rectangle, a B7 class blue/white star at least 60,000 times more luminous than our Sun.

The top left corner is marked by orange Betelgeuse, a red super-giant star of gargantuan proportions, perhaps 400 - 500 million miles in diameter. Betelgeuse is considered a strong supernova candidate, perhaps within the next 10-20 thousand years. Rigel, another high mass star, but still young, is also destined to end its days as a supernova, just a few tens of millions of years in the future, short by stellar standards.

A little distance below Orion’s belt stars are 3 stars denoting the hunter’s sword. To the naked eye nothing looks untoward, but the middle star, theta, marks one of the heavens showpiece objects – the Orion Nebula. Seen clearly as a misty smudge through smaller binoculars, through a telescope the Orion nebula can be a breathtaking sight. A swirl of nebulous cloud in the heart of which reside a trapezoid-shaped asterism from which the cluster gets its name, the Trapezium, the four “bully boys” of this stellar crèche.

The brightest members are found within 1.5 light years of each other and have estimated solar masses of between 15 and 30 times our Sun. These young OB stars are luminous X-ray sources and are responsible for much of the illumination of the surrounding nebula. The powerful UV radiation force from these stars has hollowed out a cavity in the nebula several light years across, allowing a view of them. It is Believed many of the stars forming in the cluster are no more than 300,000 years old, the brightest as little as 10,000 years. The Trapezium stars are easily seen with modest telescopes.

Upper left of Orion stand the Twins of Gemini, marked by the two conspicuous stars, Castor, and Pollux. Castor, the most northerly of the pair is slightly fainter than twin brother Pollux which shines with a pale amber lustre. Although Castor appears solitary, it is a multiple system of which the brightest two components may be separated in a modest scope. Gemini is home to the fine open cluster M35, sometimes known as the shoe-buckle cluster.

The two hunting dogs of Orion, Canis Major, and Canis Minor, dutifully follow their master across the heavens. The belt stars of Orion point down in the general direction of Canis Major and the most prominent of all night stars, sparkling Sirius, seen low to the SSE. Some distance above and left, solitary Procyon, in the lesser dog of Canis Minor, is yet another highly conspicuous winter jewel. The prominence of both stars is chiefly down to proximity; 8.6 and 11 light years respectively. Both stars have companion white dwarf stars, very difficult to spot even with quite large instruments.

Look for the faint glow of the winter Milky Way which may be noticed to the left of Orion, separating the two dogs on opposing banks. The dogs' quarry, the timid celestial hare Lepus, may be traced crouching below Orion and above the southern horizon. Lepus contains one Messier object, M79, a distant globular cluster. Within the faint starry haze left of Orion, a more modern constellation is located, the heavenly unicorn of Monoceros. Its stars are not at all conspicuous at all to the naked eye, the area looking bland, but hidden just beyond our gaze reside a multitude of star clusters and nebulae.

Below the Unicorn, Puppis, part of the now defunct constellation of Argo Navis straddles the S horizon. It is rich in galactic clusters and nebulae, including the messier objects M46, M47 and M93. The longest constellation in the heavens (or at least a section of it) occupies much of the sky lower right of Orion. The river Eridanus, the source of which rises just to the right of Rigel is marked by Cursa or beta Eridani. It then flows erratically parallel to the southern horizon before plunging through it, journeying far down into the southern hemisphere, ending at a brilliant star called Achernar.

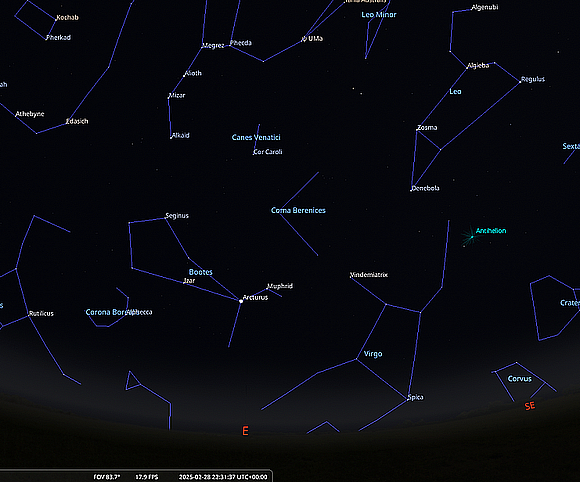

Toward the back end of February, evenings find Orion and his entourage already trooping into the west half of the sky, their places taken by an ensemble of spring constellations. The inconspicuous stars of Cancer scuttle after Gemini and mark the border of seasonal change from winter to spring. Leo the lion follows, identified by the distinctive ‘Sickle’ asterism, at the foot of which shines bright Regulus. The faint, but distinctive knot of stars marking the head of Hydra hang above the Water Snakes chief star, Alphard - the 'Lonely one', lower left of Procyon. The clock will have long struck midnight before the rest of the serpent slithers fully into view.

Post midnight, the brilliant amber hue of Arcturus in Boötes and pearly Spica in Virgo, return to the sky. Do check out Corona Borealis - the circlet of stars adjacent to Boötes, and home to the recurrent nova T Cor B. Another of the spring skies signature groups, Hercules, is only just clearing the ENE horizon. These constellations associated with spring and early summer already pushing the stars of winters tableau toward the western exit door.

The return of spring skies - sprouting from the east. End of February - 22:30hrs.

(Click for full image)

February 2026 Sky Charts

Additional Image Credits:

- Sky Charts: Stellarium Software and Starry Night Pro Plus 8

- Log in to post comments