Welcome to the WDAS monthly newsletter for January 2017: a digest of the month's latest contributions to our website. Below you'll find Society News, Sky Notes and In-Focus articles printed in full. There's also future events, and trailers for other articles which appear in full on the website - just a click away!

On the website you'll also be able to comment on articles, and if you'd like to play an editorial role in creating new content, just let us know!

Society News

Our Christmas meal at the Hare and Hounds once again proved a great success. Even though only seven members made it to the banqueting table on the date chosen (and no we didn’t lose any on the way up) did not detract from the evening.

The food was really excellent, as good as we could remember for such an occasion, the toffee cheesecake was to die for. The only slight let down was the standard of cracker jokes and toys – they do seem to get worse each year wherever you go.

I must mention the weather. We have experienced all types over the years, snow and ice, wind, fog, torrential rain. This year felt more like club Tropicana – 13 degrees at 22:30pm, just like the spicy carrot soup...phew what a scorcher. Here’s to next year’s bash... can’t wait!

We are starting to distribute Night Scenes 2017, so if you would like a copy it’s just £4 to society members, £5.50 otherwise. Cannot be certain how many copies will remain once all those spoken for have been dispatched, so don’t delay, it would make a fantastic new year's gift.

In our Solar System we find to kinds of planets: small rocky planets closer to the sun, and ice giants further out. The rocky planets (Mercury, Venus, Earth and Mars) have only three moons among them, whereas the ice giants (Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Saturn) have around ninety.

For the reason, we need to look back to the formation of the Solar System, from a giant, swirling cloud which collapsed under its own gravitational mass. As the cloud contracted, it heated-up and started to rotate faster, resulting in a proto-planetary disk hot, gas and dust rotating around a mass at its centre. The central mass, of course, became the sun; but the rest didn't immediately have the circumstances for gravity to pull together. It needed some seed.

For the reason, we need to look back to the formation of the Solar System, from a giant, swirling cloud which collapsed under its own gravitational mass. As the cloud contracted, it heated-up and started to rotate faster, resulting in a proto-planetary disk hot, gas and dust rotating around a mass at its centre. The central mass, of course, became the sun; but the rest didn't immediately have the circumstances for gravity to pull together. It needed some seed.

Near the sun, the temperature was so high that all the material was gas and couldn't form planets. A little further out there were metal flakes and fragments, and small pieces of rock; which stuck together when they collided, eventually becoming big enough to gravitationally attract matter to them, at which point we call them 'planetesimals'. They grew quickly up to the point when collisions started to break them apart. Only the largest objects survived to become the inner planets.

Outside the orbit of Mars, the temperature was low enough for ice to form in addition to the flakes and fragments. This meant more and better seeds which helped them to grow even faster. After a certain size they were able to hold on to hydrogen and helium which was abundant in the proto-planetary disk; so much so that each became something like a tiny solar system in its own right. That's how the majority of moons formed around the ice giants.

Outside the orbit of Mars, the temperature was low enough for ice to form in addition to the flakes and fragments. This meant more and better seeds which helped them to grow even faster. After a certain size they were able to hold on to hydrogen and helium which was abundant in the proto-planetary disk; so much so that each became something like a tiny solar system in its own right. That's how the majority of moons formed around the ice giants.

Between Mars and Jupiter is the asteroid belt, containing many planetesimals which failed to coalesce into planets or journey into the inner solar system because of the disruptive gravitational effects of massive Jupiter. Although it's thought that the two moons of Mars (Phobos and Deimos) are two such planetesimals which have been captured into orbit.

So then what of our own Moon? This is thought to have started out as a large planetesimal around the size of Mars, which smacked into the earth in the early solar system. The collision would have ejected so much material into earth's orbit that it eventually coalesced into a ring, and then into the Moon.

So then what of our own Moon? This is thought to have started out as a large planetesimal around the size of Mars, which smacked into the earth in the early solar system. The collision would have ejected so much material into earth's orbit that it eventually coalesced into a ring, and then into the Moon.

So in the end, we probably have just one Moon because there wasn't enough material in the inner solar system to create any more than just one, and because Jupiter tends to stop other potential moons entering the inner solar system.

The video and material for this article was made by UK Astrophysicist Sebastian

Pines, creator of the 'Astronomic' YouTube channel. You can support Seb's work creating videos that help to teach the world about astronomy by sponsoring a dollar or two per month via his Patreon page.

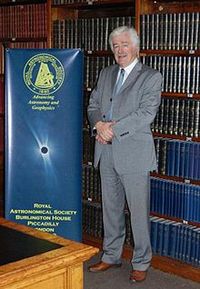

It was just as well there were plenty of savvy IT experts in the auditorium; Prof Southwood’s presentation would not open on his laptop. But after exhausting the logical possibilities, the sound techician logged-out and logged-in again, waited a near-eternity to catch the speaker's attention from an improptu time-filler talk he'd embarked-upon, we were ready to proceed.

It was just as well there were plenty of savvy IT experts in the auditorium; Prof Southwood’s presentation would not open on his laptop. But after exhausting the logical possibilities, the sound techician logged-out and logged-in again, waited a near-eternity to catch the speaker's attention from an improptu time-filler talk he'd embarked-upon, we were ready to proceed.

As far back as 1982, Prof Southwood recalled, he was present at the meeting at which the Cassini mission to Saturn stemmed. David remembers the date well – June 30th –his birthday. David was founder of what became the Space and Atmospheric Physics group, part of the team arguing for a ‘bolt on lander’ which eventually would be funded by ESA as NASA was reluctant to do so.

The lander was not destined for Saturn, but its mysterious and largest moon Titan. Huygens was born. Prof Southwood was also leader of the team which developed the magnetometer on the main Cassini spacecraft.

The lander was not destined for Saturn, but its mysterious and largest moon Titan. Huygens was born. Prof Southwood was also leader of the team which developed the magnetometer on the main Cassini spacecraft.

In 1996 Cassini was finally launched, the largest planetary probe to be sent into space.

In May 2001 David became Director of Science at ESA, and under his directorship oversaw 3 low cost ESA planetary missions; Smart 1 and Mars Express in 2003 and Venus express in 2004. The same year, in June, Cassini finally reached Saturn. 2004 also saw the launch of ESA’s ambitious Rosetta mission to comet 67P. It was a busy time for David.

Back at Saturn, Cassini had to undergo a very risky manoeuvre in order to enter the correct orbit – a ring plane crossing – twice! David recalled how the tense the control room was at the time, the date, June 30th. On Christmas day 2004, Huygens was jettisoned from Cassini, taking 3 weeks to reach Titan, no communications were possible during this period before it arrived on Jan 14th. It then survived the 2 hrs 27minute descent through Titans hazy atmosphere, landing on the frozen surface.

Titan is Saturn’s largest moon and second largest in the solar system and has a substantial atmosphere, the pressure being 50% more than Earth’s composed chiefly of nitrogen, hydrogen, carbon and methane, but not much H20. On Titan itself methane exists at the triple point, similar to how water exists on earth, taking the form of a gas, solid or a liquid. Huygens had to be designed for any eventuality on landing. Oxygen is frozen out on titan, not leached out like on earth 1 billion yrs after its formation. Titan is therefore similar to a primordial earth, so the opportunity to study such a world, conducting real science, even for a short period, was too good to miss for the small increase in weight of the Cassini mission. The mission wasn’t flawless, one of the cameras malfunctioned, but Huygens did transmit for 72 minutes before contact was lost, data which is still being analysed today.

It turns out Huygens landed on a methane shoreline, it remains the most distant standing artefact built by humans- something Prof Southwood is very proud of.

In 2008, Southwood became ESA’s first Director of Science and Robotic Exploration, before retiring from ESA in 2011 becoming president of the Royal Astronomical Society 2012-2014.

Rosetta finally reached the wonderfully shaped comet 67P in Aug 2014, David joked if they had known the actual shape of the small comet before launch, and they would not have contemplated setting down a Lander on its surface. As it was they were there, so why not have a bash. As we know in November of 2014 Philae made it...just, touching down 3 times before coming to rest, lodged in a crevice, the first manmade artefact to land on a comet. It was another proud moment in David’s life.

David then showed several images of various dignitaries, including the French president, meeting and greeting various ESA scientists involved in the Rosetta and Philae mission. Yes, it was big news in the UK, it was even bigger news on the continent, considered a really significant milestone for ESA and scientific exploration in general.

As director of science at ESA when Rosetta launched, David insisted that a small micro disk was fixed to it, for at the end of Rosetta’s mission to study 67P, Rosetta was destined to become the 2nd artefact to ‘land’ on a comet, its last journey. Etched on the micro disk is the 1st chapter of Genesis of 3 religions in 1000 languages and dialects – a 21 century Rosetta stone.

Mary Somerville

Allan's chosen subject this year Mary Somerville-the Lady Mathematical Astronomer, one of the first serious scientific woman of the 19th century, a ‘grand amateur', of independent means who could pursue her passion to a professional level. In and an age when scientific work was undertaken by men, very few women could be counted as equal to their male scientific peers.

Mary was born to Lt. George Fairfax and Margaret Fairfax in 1780 in Scotland. Her childhood was spent exploring the seaside of her hometown of Burntisland near Edinburgh. Her father was a Vice Admiral in the navy and whilst stationed in America during the war of independence was written to by one George Washington, who thought he may be related to the Fairfax’s. Back home Mary grew up very much ‘a tom boy’. She had a sharp sense of humour and could swear like a trooper - something learned off her uncle who had served in India. An algebra problem in a women's fashion magazine introduced her to mathematics. (Couldn’t imagine Vogue running anything like that nowadays) She was curious what the symbols meant. It was considered improper for a young lady show am interest in mathematics, and she had to secretly ask her brother's tutor to buy her a copy of Euclid's Elements, after overhearing that Elements formed the basis for understanding astronomy and other sciences. Far from being encouraged in reading, members of her family criticised her for spending time on this unladylike occupation, so she read in secret by candle light on a night, until she was caught out.

After retiring on a modest pension her father thought what Mary needed was a husband, so in 1804 when aged 24, Mary married a distant relative, Samual Greig, a Russian diplomatic naval attaché. He had a low opinion of Mary, and did not encourage or support her in her thirst for knowledge. The marriage was short; he died of fever a few years after they were wed. The death of her husband, although difficult and tragic, did however; afford Mary an opportunity quite rare to women of her time.

Mary found that widowhood and a comfortable inheritance had left her both emotionally and financially independent. She was free to study according to her personal convictions and returned to Edinburgh where she was given private tutorials in mathematics. She corresponded frequently with Scotsman William Wallace, who, at the time, was mathematics master at a military college.

Mary Somerville in Middle-age

Mary mastered J. Ferguson's Astronomy and became a student of Isaac Newton's Principia, reading Newton's Principia and, and at Wallace's suggestion, Laplace's Mécanique Céleste and many other mathematical and astronomical texts. She learned to the very highest level - to the French thinking on maths and was brilliant at it. She won prizes for solving maths puzzles in journals including a silver medal from the mathematical journal –The Mathematical Repository; she also acquired a 5ft Gregorian telescope.

Then in 1812 Mary married William Somerville, a doctor, and another distant family relative. William was extremely proud of Mary. The family moved from Edinburgh to London. Her husband was elected to the Royal Society and Mary and William moved in the leading scientific circles of the day. Their friends included George Airy, Maskelyne, John Herschel, William Herschel, George Peacock, and Charles Babbage. In addition they met with leading European scientists and mathematicians who visited London.

In 1817 William and Mary visited Paris and were introduced to the leading scientists there by Biot and Arago (whom they had met in London). Mary met Laplace, Poisson, Poinsot, Emile Mathieu and many others. All thought her to be charming and quite brilliant. They enjoyed the theatre, opera, visiting the fashion houses and going to balls, she became a real socialite. They then continued south, where she was fated in Germany, then onto Florence, Rome, Pompeii, she even had a private audience with the Pope...She was a Scottish protestant!

In 1824 en route through Italy, William was appointed as a physician at the Royal Hospital in Chelsea. Returning to London, Mary and William continued close contact with their many scientific friends. Mary Fairfax Somerville's scientific investigations began in the summer of 1825, when she carried out experiments on magnetism. In 1826 she presented her paper entitled "The Magnetic Properties of the Violet Rays of the Solar Spectrum" to the Royal Society. The paper attracted favourable notice and, aside from the astronomical observations of Caroline Herschel, was the first paper by a woman to be read to the Royal Society and published. She became known for her exceptional expository talent, even so, woman were still refused entry in the great libraries and noble institutions of the country. William had to write down whole chapters of books for Mary.

Then in 1826 Lord Brougham, Scottish Barrister, speaker of the house of Lords, Lord Chancellor and mad keen amateur scientist, on behalf of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge, began correspondence with Mary through her husband, as social convention dictated, to persuade her to write a popularised rendition of Laplace's Mecanique Céleste and Newton's Principia. Mary undertook the project in secrecy. In 1831 ‘A Mechanism for the Heavens’ was published, more of a reinterpretation than a translation. It caused a sensation and the book became a required text for higher mathematics students. Her books were used to teach ‘real tuff science’ at Cambridge University.

Mary Somerville spent most of 1832-33 in Paris where she renewed old friendships with the mathematicians there, and where she worked on her next book; The connection of the physical sciences -an account of physical phenomena and connections among the physical sciences. This was published in 1834. Her discussion of a hypothetical planet perturbing Uranus in the sixth edition (1842) of this work led John Coach Adams to his investigation and subsequent discovery of Neptune. The book also fired the imagination a young Charles Darwin.

These projects helped firmly establish her in intellectual circles. She and Caroline Herschel were elected in 1835 to the Royal Astronomical Society, the first women to receive such an honor. She was granted honorary memberships to the Société de Physique et d'Histoire Naturelle de Genève (1834), The Royal Irish Academy (1834), and the Bristol Philosophical and Literary Society (1835) and eleven Italian scientific societies between 1840 and 1857. Sir Robert Peel, British prime minister from 1834-35 and again from 1841-46, awarded her a civil pension of 200 per annum.

In 1838 William resigned his appointment at Chelsea and in 1839 the Somerville’s returned to Italy, where amongst other exploits Mary climbed Mt Versuvius just a few weeks after it had erupted. Then in 1848, at the age of 68, Mary published yet another book in two volumes - an A-Z of the Earth’s surface entitled Physical Geography, the first modern work on the subject. It was an enormous best seller and was widely used in schools and universities until the early 20th century.

Many further honours were given to Mary as a result of this publication. She was elected to the American Geographical and Statistical Society in 1857 and the Italian Geographical Society in 1870. In 1870 the Royal Geographic society presented her with its Victoria Gold Medal.

Her last scientific book; Molecular and Microscopic Science, which was published in 1869 when Mary was eighty-nine, and was a summary of the most recent discoveries in chemistry and physics. In that same year she completed her autobiography, of which her daughter, Martha, published parts after her death. Even at the age of 90 Mary and Sir John Herschel, who himself was 75, were corresponding on why Lobsters glow in the dark - and if one could take a spectrum - truly incredible. In November of 1872 aged 92 Mary finally passed away. Apparently shortly before her death and befitting of an admirals daughter, having outlived her husband, most of her friends and all but one child, Mary is reported to have said - “ I am ready to go now, I am just waiting for the Blue Peter to be raised and I shall journey to distant shores, to make and renew acquaintances”

Mary Somerville was a strong supporter of women's education and women's suffrage. John Stuart Mill, the British philosopher and economist, organised a massive petition to parliament to give women the right to vote, he had Mary put her signature first on the petition. Somerville College in Oxford was named after her in 1879 because of her strong support for women's education, a fitting tribute to a quite extraordinary woman.

Events

Observe the night sky with us at the Bruce Observatory, Whitby School

Observe the night sky with us at the Bruce Observatory, Whitby School

Observing Nights are held weather permitting: check for a relatively clear sky before leaving home. If in doubt, Mark can be reached on 07886069339

Please note the college drive gate is now operated via a electronic key code - so anyone wishing to attend must be at the car park at the top of the drive by 19:00hrs - unless an arrival time has been arranged with Mark/Keith.

Observe the night sky with us at the Bruce Observatory, Whitby School

Observe the night sky with us at the Bruce Observatory, Whitby School

Observing Nights are held weather permitting: check for a relatively clear sky before leaving home. If in doubt, Mark can be reached on 07886069339

Please note the college drive gate is now operated via a electronic key code - so anyone wishing to attend must be at the car park at the top of the drive by 19:00hrs - unless an arrival time has been arranged with Mark/Keith.

Whitby Youth Hostel - East Whitby - rear of Abbey vistor centre.

Whitby Youth Hostel - East Whitby - rear of Abbey vistor centre.

Observe the night sky with us at the Bruce Observatory, Whitby School

Observe the night sky with us at the Bruce Observatory, Whitby School

Observing Nights are held weather permitting: check for a relatively clear sky before leaving home. If in doubt, Mark can be reached on 07886069339

Please note the college drive gate is now operated via a electronic key code - so anyone wishing to attend must be at the car park at the top of the drive by 19:00hrs - unless an arrival time has been arranged with Mark/Keith.

Whitby School, Prospect Hill site, Main block, Room H1 (first along corridor from Hall).

In our monthly meetings, we review the night sky for the upcoming month using a Planetarium program, have talks and presentations on astronomy and space topics, and discuss future events. New members are welcome.